Two birds, beautiful of wing || On Mundaka Upanishad (2021)

द्वा सुपर्णा सयुजा सखाया समानं वृक्षं परिषस्वजाते । तयोरन्यः पिप्पलं स्वाद्वत्त्यनश्नन्नन्यो अभिचाकशीति ॥

dvā suparṇā sayujā sakhāyā samānaṃ vṛkṣaṃ pariṣasvajāte tayoranyaḥ pippalaṃ svādvattyanaśnannanyo abhicākaśīti

Two birds, beautiful of wing, close companions, cling to one common tree: of the two one eats the sweet fruit of the tree, the other eats not but watches his fellow.

~ Verse 3.1.1, Mundaka Upanishad

✥ ✥ ✥

समाने वृक्षे पुरुषो निमग्नोऽनिशया शोचति मुह्यमानः । जुष्टं यदा पश्यत्यन्यमीशमस्य महिमानमिति वीतशोकः ॥

samāne vṛkṣe puruṣo nimagno'niśayā śocati muhyamānaḥ juṣṭaṃ yadā paśyatyanyamīśamasya mahimānamiti vītaśokaḥ

The soul is the bird that sits immersed on the one common tree; but because he is not lord he is bewildered and has sorrow. But when he sees that other who is the Lord and beloved, he knows that all is His greatness and his sorrow passes away from him.

~ Verse 3.1.2, Mundaka Upanishad

✥ ✥ ✥

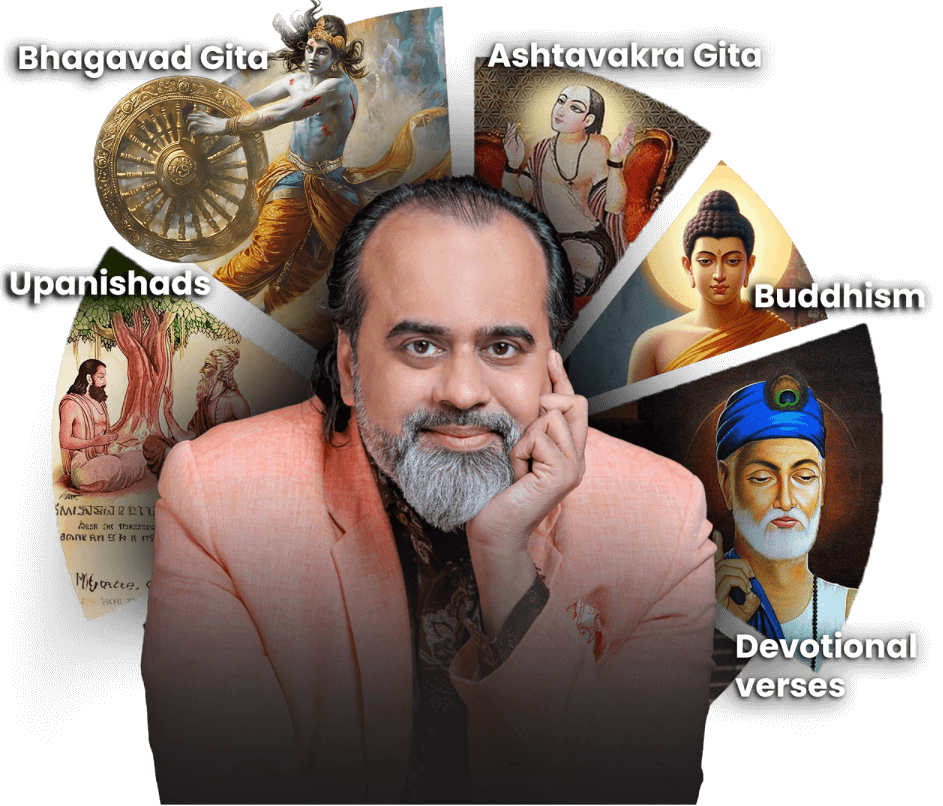

Acharya Prashant (AP): Now we initiate the third Mundaka and come to one of the most popular verses from the Upanishadic treasure trove.

“Two birds, beautiful of wing, close companions, cling to one common tree”—closely related to each other, sit on one common tree. “Of the two one eats the sweet fruit of the tree, the other eats not but watches his fellow”—the other bird.

Two birds, both beautifully winged, both of beautiful feather, sit next to each other, and they both are related to each other. Out of these two birds, one sits and eats the fruit of the tree, while the other just watches without eating. And what is he watching? The bird that eats.

These two birds have been the subject of great deliberation. Who are these two birds? These two birds are close companions, they carry the same name. What is the name that they carry? ‘I’.

So, there are two ‘I’s. These two birds represent the two ‘I’s that there are. So, they carry the same name, they belong to the same family, yet there is a great difference. There is one ‘I’ that is lost in the world, absorbed in the world, and is busy consuming the world; the fruit is sweet to this bird. And then there is another ‘I’ that has no inclination towards consumption, it just watches.

Now, when you talk of birds, then the consumption is physiological. When you talk of ‘I’, the consumption is psychological. The ‘I’ consumes the world to have an identity; it cannot exist without an identity. The incomplete ’I’, one of the birds, the first bird, keeps nibbling at the world because it is forever hungry.

And then there is another ‘I’ that is psychologically complete. Well, physiologically even this bird might need to poke at the fruits—only physiologically; psychologically, this bird is complete. Psychologically, there is an ‘I’ that is totally complete and it does not need the world for its sustenance; therefore, it would neither get attached to the world nor would it destroy the world.

The analogy of the two birds in Mundaka Upanishad is extremely beautiful, very, very deep and meaningful, and very popular as well. People read this and, as much as they are baffled by this, they still enjoy this, because there is something in this metaphor that appeals very intuitively to us. Even if we do not know of the two ‘I’s, we still sense that something very important is being spoken of.

Now, the next verse is in continuation.

“The soul is the bird that sits immersed on the one common tree”—immersed in the sense that he is absorbed in the world, attached to the world. “But because he is not complete”—the word here used is ‘*aniśa*’ meaning ‘not *iśa*’.

“But because this soul is not complete”—what is referred to as the soul in English here is the puruṣa in the verse, nimagna puruṣa , and that has been very loosely translated as the immersed soul.

“Because he is not lord he is bewildered and has sorrow. But when he sees that other who is the Lord and beloved, he knows that all is His greatness and his sorrow passes away from him.”

So, the bird that is busy consuming the world is the Puruṣa , Puruṣa bewitched by Prakriti (physical nature), Puruṣa captivated by Prakriti . The fruit, the tree, the branches, the entire scenario, the whole jungle in the setting, what do they collectively represent? Prakriti . And in the middle of this Prakriti sits the Puruṣa bird—and this Puruṣa can also be called as aham (ego)—and this Puruṣa has been totally enamoured by Prakriti . So, he is going to Prakriti , this way, that way, and so on, and in his bewilderment, he suffers, says the verse.

How does he lose his suffering? Now, it is very beautiful, very, very instructive here. It says: By looking at the one who does not tend to consume; by looking at the one who is complete, and therefore lovable, and therefore the Lord. Looking at that one, this bewildered one, enchanted one realizes greatness—the greatness of the other one and his own potential greatness—and therefore gains freedom from suffering.

Now, it is quite instructive. You see, we often say that the Lord must look at us. “Oh Lord, why are you looking the other way? Why don’t you look at me and relieve me of my sufferings?” But the verse says you get freedom from your sufferings when you look at the Lord.

The Lord is sitting beside you. The Lord is always watching you. The Lord is the Sākṣī . The Lord is the ‘I’ you call as Ātman (Self). These two have the same name, right? ‘I’. One is aham , one is Ātman . The Lord is always looking at you because it is in the nature of the Lord to know. But when will you look at the Lord?

When you look at the Lord instead of looking so much at Prakriti , that is when you gain freedom from suffering. Beautiful.

So, these two birds are there. Take it as a picture board. These two birds are there; one is busy consuming, enjoying fruit, and the other one is just watching. But the first one, irrespective of how much fruit he consumes, is still suffering and bewildered. And when does he lose his suffering? When he looks at the one who is not consuming at all.

So, when you come to see that the satisfaction that you want to derive from the fruit is actually a pre-existing thing already available to the one who does not go after the fruit at all, that is when you lose the fruit and gain freedom.

So many lessons are contained here, including the importance of the right company. If you want to be liberated of your existing ways, then you will have to seek the company of someone whose ways are different. Looking at him will give you the strength and the trust to drop your ways. Otherwise, there is just too much fruit around to let you really know the Truth. If one type of fruit disappoints you, there is another one to attract you, and then the next one, and then the next one.

No fruit is ever going to reveal to you that even all the fruits taken together cannot give you what you really want, but the company of the right bird can deliver you liberation.

The world is not to be used for existential contentment. The world can give you food, clothes, shelter, money, pleasures of the body. All these things the world can give, and to a limited extent the world is obviously useful. But the world cannot give you yourself; the world cannot give you an identity. If the world is giving you your identity, then you don’t exist, right? You are the world, then. Where is your independence? Where is your independent existence?

So, being independent of the world, look at the world. Even if at the bodily level there has to be consumption, you consume the world as an entity independent of the world. That is the import of these two beautiful verses.

Questioner (Q): So, the bird that is consuming the fruit, the hungry ‘I’, will leave its ways when it sees the witnessing bird. How does this bird come to a point where it looks at the witnessing bird?

AP: No, there is no method to it really. We cannot make this into an order or a system. When will the first bird look at the other? We do not know. What is the process, what is the method? We do not know. How to make the first bird look at the witnessing bird? We do not know; of that we have no idea. But what we know is: when the first bird looks at the Lord bird, the witnessing bird, then a great change will happen. That much we know. Now, how to make it happen? We do not know.

People keep speculating. Somebody says that when the first bird would get diarrhea from eating so much fruit, then he would look at the second bird; when the first bird would be tired of eating a lot, then he would look at the second bird; when the first bird would have his stomach totally full and bloated, then he would look at the second bird. We do not know. All these are just theories.

What we know is: if the first bird is hungry of liberation from his gnawing frustration, then he will have to look at the second bird. And the second bird is very easily available to be looked at, not far away. You just have to attend to the right one. There is the fruit, and there is the bird in your neighborhood. It is as easy to look at the other bird as it is to look at the fruit.

You have to decide when you will stop looking at the fruit and turn your attention towards the witnessing bird. It is a matter of choice, not a matter of circumstance. What you are asking for is a template that defines the circumstances that make the first bird look at the second. We do not know—why? Because it is a sovereign choice of the first bird. Only the first bird knows when it will look at the second bird.

That’s how easy it is. All that you have to do is make a choice; you have to choose to look at the second bird. Looking at the second bird, sometimes you will say that the circumstances facilitated, at other times you will say that the circumstances opposed, resisted; but the fact is, it is not a matter of circumstances, it is actually a matter of choice.

When will you make a choice? When will you make the right choice? Only you know it. No method can dictate your choice. Your own sovereign will is the chooser. One can only be pleaded to. The rest is your decision.

See, if it becomes a matter of a system or a formula, then it is like the overhead tank overflowing. We know that after such a particular volume of water, it starts overflowing. So, then we can say that after the bird has eaten 2.2 kilograms of food, it will start overflowing, and it will look at the adjacent bird. It is not that way, because then there is no space for your choice; then it is a very mechanical thing. We know when the tank will start overflowing, don’t we? We know all the variables. We know the flow-rate of water, we know the capacity of the tank, so we know when it will start overflowing. Now, there is no space for conscious choice in this. Life does not operate like that.

There are people who don’t choose to look at the brother bird even after devouring the entire forest. They have consumed and burned down the entire forest—they still don’t want to look at the beautiful bird sitting next to them; they don't want to. And there are those who consume only a little, and they know that this won’t do. They start looking at the beloved lord bird.

You decide.

Q: Does this also mean that the incompleteness of the first bird is his choice? The bird is complete, but he chooses to be incomplete?

AP: Wonderful. Yes.

Q: So, incompleteness can be removed by choosing completeness? But would it not then become just an idea, a framework?

AP: All kinds of incompletenesses are ideas. Completeness is not an idea. If completeness is an idea, it is another kind of incompleteness. If completeness is merely an idea, then it won’t penetrate into your life; then you won’t look at the other dimension, the other bird. Then you will just keep thinking of completeness. When completeness is more than an idea, then it becomes real action, pure action; then you drop the fruit and embrace the real one.

The two birds are one. They are not two birds. Do we see this?

You know, this is what I mean when I say that when you are a lover of Truth, when you are in the Truth, then the entire world becomes just the Truth to you. Can you visualize the sage just standing close to this tree one early morning and looking at these two birds? And these are just two ordinary birds, you know, any two birds. They are chirping, twittering. One of them is busy eating fruit, the other is just silently watching—and these are just two birds. But the sage is so deeply rooted in Truth, so much in love with the Truth, that he looks at these two birds and he immediately realizes something of a very high order.

Now, these two birds have not really been planted by existence to teach the sage a lesson. Their occurrence on the tree that morning is just accidental; they happen to be there on the tree. There are so many birds that are there, on so many trees, on so many mornings. But who looks at them and comes upon a great truth? Well, hardly anybody. But the sage does.

That is what starts happening to you when Truth is your first priority: Irrespective of the direction you are looking at, there is something to teach you a lesson, to take you to the Truth.

Can you visualize that sage? There is that tree, an ordinary neem tree, and one of the birds is busy nibbling at the neem fruit, the other is just watching. And there is a subtle and beautiful smile dancing on the sage’s face, and from that smile arise these two verses. Timeless!

The world is Brahman , is it not? But the birds are so ordinary! Still, the world is Brahman .

Depends on you.

Two ordinary birds will become the ambassadors of Truth, provided you love the Truth.