The World of the Worldly Man Hates the Truth

समदुःखसुखः पूर्ण आशानैराश्ययोः समः । समजीवितमृत्युः सन्नेवमेव लयं व्रज ॥

samaduḥkhasukhaḥ pūrṇa āśānairāśyayoḥ samaḥ samajīvitamṛtyuḥ sannevameva layaṃ vraja

Equal in pain and in pleasure, equal in hope and in disappointment, equal in life and in death, and complete as you are, you can go to your rest.

~ Chapter 5, Verse 4

✥ ✥ ✥

स्वप्नेन्द्रजालवत्पश्य दिनानि त्रीणि पञ्च वा । मित्रक्षेत्रधनागारदारदायादिसंपदः ॥

svapnendrajālavatpaśya dināni trīṇi pañca vā mitrakṣetradhanāgāradāradāyādisaṃpadaḥ

Look on such things as friends, land, money, property, wife, and bequests as nothing but a dream, a magician’s show lasting three days, five days.

~ Chapter 10, Verse 2

✥ ✥ ✥

Questioner: Sir, I’ve never experienced this equal state nor have I ever lived like people and objects are temporary. I understand they are temporary in an intellectual sense but that has not brought much change in my life. Please guide this so-called family man, worldly man, who is able to satisfy neither family nor God.

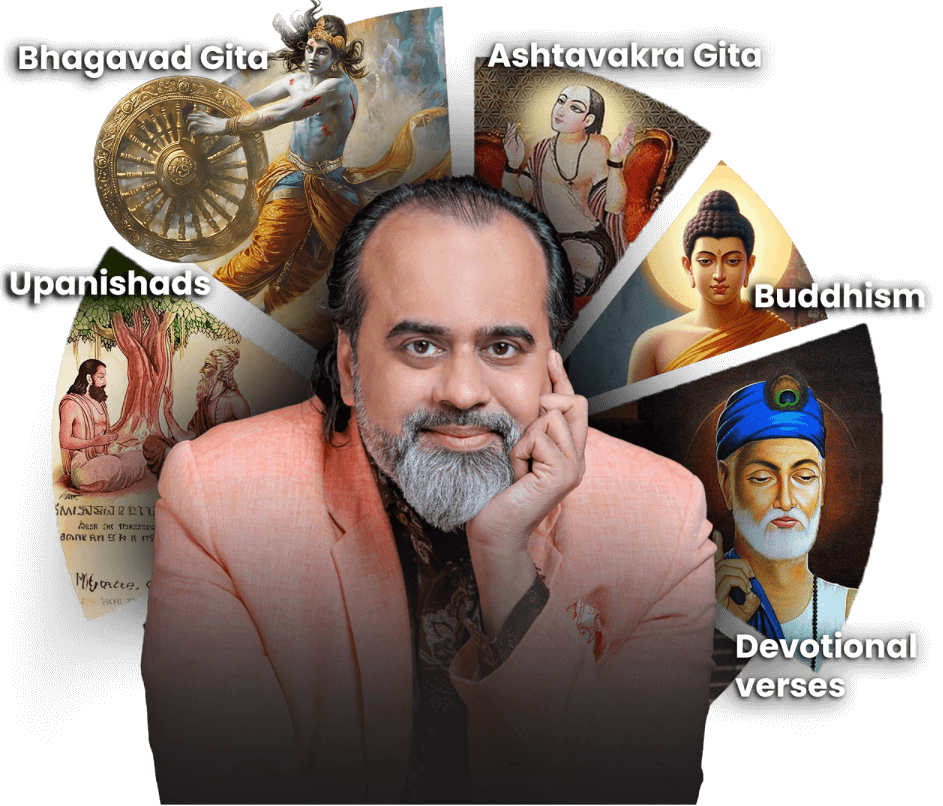

Acharya Prashant: These are descriptions. These are just descriptions—these are not teachings. A point comes when even teachings become unnecessary. They look childish. At best, they resemble a joke; at worst, they sound like insults.

I am thirsty, very very thirsty. You show this to me (picking up a glass of water) . Then, would you also teach me, “Drink it, drink it”? If you have to teach me—the thirsty one—to drink it, then either my thirst is a fraud or your water is a sham. I’m really thirsty, and if the water is really pure, then merely showing the water is enough.

Equally, if I am here and I claim that I am really thirsty, then you do not need to motivate me to go to the river; you merely describe the way. Having described the way, you would not even bother to say, “Go!” If after all the description you still have to say, “Go,” then that is a blemish upon the power of your description.

So, when it comes to purest utterances, they are merely declarations, descriptions, grand announcements without a purpose, without a context, without a background. They would not say, “Now, that we have told you the Truth, this is what you ought to do with it.” None of that. They’ll not come with a user manual, the Upanishads.

The Upanishads just are. They will not tell you how to use them. They are only for the ones who know what the use of peace is. Who knows what the use of peace is? The one who is burning with peacelessness. The thirsty one knows what the use of water is. Having shown him the water, you do not have to describe to him the H2O molecule. You don’t have to tempt him to come to the water. The news is enough.

The passengers are waiting at the platform. The announcement is enough. “The train is arriving.” Does the announcement also say, “Now, the passengers must rush towards the train or their respective bogies”? Does the announcement include that? If you really want to depart, the news is enough. But if you have made your little hut on platform number eight—as many people do—the announcements come and go, you never go. There are many who live on the platforms. Lao Tzus come and go, Ashtavakras come and go. Day and night, there are announcements, and every announcement heralds an opportunity. The ones that don’t have to go, don’t go. Then, there are the ones who are seen running after the trains huffing and puffing but somehow catching.

So, does this tempt you? If this does tempt you, then proceed. If it doesn’t tempt you, then seek the company of some of those who you see as eager to board the train. Ask them, “Why do you want to depart? I don’t want to depart. I’m a worldly man, I want to stay put.” If it hurts you too much, do not seek instruction from them, rather seek to convert them. Present your own example to them and tell them how you prefer staying on the platform rather than departing. Try to convince them. Maybe you will save a few of them some unnecessary hassle. Trains are overcrowded anyway; if you can convince a few aspiring passengers not to board, maybe you are doing everybody some good.

But do get into a conversation. Do ask them what it is that charms them? Why do they look at the horizon with such thirsty eyes? Why do they put their ears to the track and want to listen to the beat of the approaching train? Why are they so eager? You tell them why you are so lukewarm, and you ask them why they are so much in heat. Engage them. We are not saying that it’s a pre-decided debate. Maybe you will prevail. Maybe you would convince an Ashtavakra not to depart. All I can say is begin the game of engagement and play honestly. If you see that what they are doing is the right thing to do, then don’t wait for the next train; hold their hand and board.

You have been young, and even in a worldly way, one can show you the image, the picture of the most beautiful woman but one cannot make you fall in love with her. One can read out to you the most touching poem but one cannot force you to admire her. “She walks in beauty like the night of cloudless climes and starry skies.” Did something happen? If nothing happened, then it cannot be made to happen, not because the situation is hopeless but because you are determined.

Therefore, an Ashtavakra is far wiser than an ordinary teacher who teaches through instruction. Ashtavakra says, why waste energy? Instructions are anyway not useful beyond a point.

You can instruct a fellow to come and sit down in front of you and hear you out but you cannot instruct a fellow to resonate with you. That is beyond instruction. The resonance would happen only when the fellow wants it to happen.

“Equal in pain and pleasure, equal in hope and in disappointment, equal in life and in death, and complete as you are, you can go to your rest.” Now, neither are you equal in pain and pleasure nor are you equal in hope and disappointment, nor are you equal in life and death, nor are you complete, nor are you restful. Then, why is Ashtavakra telling all this to you? He is saying if this sounds charming enough, then, “Come my way, boy; else you can have your way.” He says, “You like what you see? Then come over. You like what you hear? Then come over. Else platform to you, you to your platform.”

There is a way of the accomplished teacher. There is a way of the teacher who has seen the futility of trying too much with the student. Teachers who are just beginning are overloaded with the energy of amateur enthusiasm. Having got it, they think it can be transmitted equally easily. So, they strive; they try very hard. The ones like Muni Ashtavakra are veterans, seasoned professionals. They know that it doesn’t help to flog a dead horse. The horse has probably come to enjoy the flogging. Leave it to itself and maybe then it would run. If it doesn’t run, it doesn’t have to run. All horses are entitled to their own self-determined quota of flogging. Who is an Ashtavakra or any other teacher to make a horse run against its own free will? So, they won’t flog the horse. They would simply whisper in the horse’s ear, “There is green grass on the other side of the mountain,” and then they leave it to the horse.

Real teachers are real non-doers. They won’t make the effort of cutting the grass and bringing it to the horse. They would say, “Enough has already been done. The rest is upon the horse.” Maybe the horse has fallen in love with some yellow and pale dead grass right where he is lying. It’s okay. The horse is entitled to all kinds of experiences.

It’s a fine art: How much must one be exposed to therapeutic radiation? If the exposure is too little, then there is hardly any therapy; if the exposure is too much, it’s worse than having little therapy. It’s a fine art.

“Friends, land, money, property, wife, nothing but a dream, a magician’s show lasting three days, five days.” He doesn’t say, “Hence…” He leaves the rest to your wits. You decide. He has told you what these things are. The rest is upon you. You are welcome to scrutinize the fact of his utterances whether these things are or are not for three or five days—that much you can scrutinize. But after the scrutiny, your sweet will. Having seen that these things are indeed ephemeral, your free will.

This is the point beyond which no scripture works. This is the point beyond which no teacher, no guru can help you, rather would help you. This is the point to which you must be brought and left alone. This is the point after which either your suffering works or your deep prayer. Either you should be so badly suffering that you refuse to let the teacher go when he is about to drop you and disappear, or you should be so convinced about the need to depart that you pray to get the decision, the motivation, the energy, and the legs to run.

What to do then? I’ve already told you. Engage these people, converse with them. See what Muni Ashtavakra has to say to you, and see what you have to say to him. After all, if you want to stay put on the platform, you must be sure of yourself, right? If you are sure of yourself, why shy away from an honest conversation? If your reasons are genuine, they will hold out; if they are not genuine, then they must burn out. Keep talking to them. Maybe some of what charms them would rub off on you. That’s why the sages have emphasized so much on the importance of the right company.

Be in the company of the one who is found a lot in the company of the One.

How do you know that you must be with somebody like Ashtavakra? Because Ashtavakra is continuously in the company of the One. That’s how you must also choose your friends and partners. The one you spend so much time with, is he usually found in the company of the One, or is he someone who is rarely found in the company of the One?

You’re saying you are a family man, a worldly man. What kind of world is yours? In your world, you are at the center, right? You are not talking of the world, you are talking of your world. When you say you are a worldly man, you are talking about your personal world. What’s your personal world full of? Who are the residents of your personal world? You aren’t talking of the eight billion people on this planet. You aren’t talking of the trillions of other sentient beings on this planet and, obviously, you aren’t talking of the myriad forms of consciousness that might be existing throughout this universe.

When you say the world, when you say you are a worldly man, you mean five people, ten people, 20 people, 50 people, 100 people—these are the people that constitute your world, right? It’s a very misleading expression, you know, ‘the world’ because it is never the world, it is always my world. Nobody lives in the world. There is no subjectivity that is being admitted. We act as if there exists an objective world, the world but there is nothing called an objective world. It’s always your world, and that’s why your world is very very different compared to your neighbor’s.

So, who is it that fills your world? Who all make up your world? Are they people like Ashtavakra? When you say you’re a worldly man, what you essentially mean is that you are in the company of a few people, right? When you say you are a worldly man, what you mean is that you are in the company of a few people. These are the few people that constitute your world. So, it’s a question of the company. Whose company are you exposing yourself to?

I’ve already given you a very easy thing to use as a test. The one you are with, is he with the One? See where your time is going. Look at the faces that occupy your consciousness. Look at the ones you are conversing with day in and day out. Conversing whether in your imagination, physically, or on your mobile phone—who are these people? Are they in the company of the One? If they are not, then rest assured their company would pull you away from the company of the One. Equally, the company of an Ashtavakra would pull you towards the One.

If you are finding yourself distanced from the One, now you know the reason: kusaṅgati (bad company). And it won’t announce itself as a bad company; it comes in different names. It comes with nice, fair, clean, polished faces. It won’t say, “Neither do I belong to Him nor would I let you belong to Him.”

The quality of your company can be assessed only by the impact it has upon you.

You have to be very careful because there is a clear conflict here. Declaring yourself as a worldly man—and your world does not include Ashtavakra, does it?—you are asking me, why don’t the utterances of the knowers, the sages bring about real change in your life? Because they stand outside of your immediate world. They are not part of your intimate world. Your intimate world consists of people who not only have nothing to do with the sages but who might actually be in active or passive hatred of the sages. Those are the people who constitute your inner circle.

You do not need to judge a person by his words alone. Want to check the quality of the people you are keeping as company? Check just one thing: Whose company do they love? Ask this question: “Who is the friend of your friend? Is your friend amongst the one closest to the One or is your friend amongst the ones who are farthest from the One?”

Your friends are your world, and your world is your identity. That’s what you are calling yourself as, “I am a worldly man.” I’m just parsing that. What does it mean to say ‘I am a worldly man’? You mean to say that you are in the company of a few people. That’s what you mean. Even kids know that.

In a class, let’s say a normal school—the kind of school we all have been through—a normal, usual school, and the teacher always has her favorites. If you are a newcomer to the class, you immediately smell who the favorites of the class teacher are and then you want to be friends with them. Even class 4 students—not divine students, very worldly kids—know how to reach the teacher. Don’t you know? The newcomer also smells that there is a particular gang in the class that the teacher does not quite approve of. If the newcomer decides to belong to that gang, then the newcomer has already sealed his fate.

The gang is a world, and you are a worldly man. Why do you so stubbornly want to belong to the gang that the class teacher dislikes? You knew better than that when you were a class 4 kid. How have you forgotten even basic commonsensical knowledge? God is the class teacher, Ashtavakra is the frontbencher she loves. If you want to curry favor with the class teacher, better make friends with the frontbencher, not the backbenchers who are seen in the class once a month, who appear in the class only on special occasions.

“You know, it’s Independence Day; let’s go to school.” You aren’t coming to the school for the sake of learning or for the sake of the teacher. You are coming for the sake of laddoo (Indian sweet). What are you here for—for learning or for laddoo ? Ask yourself. If you’re here for the learning, you would’ve been seen quite frequently here; but if you were seen here only on special days, it means you aren’t here for the teacher, you are here for the laddoo . Examine your world.

It’s a conflict, we said. You see, somebody has to lose. You can’t have two winners in this. Somebody will be brought to his knees and somebody will hang his boots.

If you are at a party, and the faint music of a fakir outside the party venue enthralls you, one of the two has to win because the fakir won’t enter the party. The fakir won’t enter the party nor would the party admit the fakir. You have to belong either here or there. The party is loud, the fakir’s music is faint; you are inside, the fakir is outside. The odds are greatly against the fakir, but let’s see. Strange things happen.

The party is your world. Question yourself again and again on this: Does your world really have to be like this? You aren’t talking about an objective reality that you can’t breach, you’re talking about your self-created nest. You’re talking about relationships that you, on your own volition, walked into and, on your own volition, are sustaining on a daily basis. You’re talking of jobs you carry out by way of proper, legal agreements. You aren’t talking of things that are insurmountable. You aren’t talking of the indispensable realities of life. You’re talking of choices, mind you. You’re talking of things very much within your control.

You push the buttons, you pull the levers, you board the train, you swipe the card, you sign the letters—all that requires your conscious agreement. Your world is nothing but a reflection of your deliberate agreements. The agreements are in the mind, and therefore, invisible, subtle.

What you call as your world is a representation of the inner agreements that you make.

Where is Ashtavakra in your world except on the four days of MAG (Spiritual course run by the Advait Foundation)—not four days; one or two days when you choose to send over a question. 28 days of the month, is he there in your world? No, because you’re a worldly man. Even on the two days when you send over your questions, is he really there with you the entire day? So, in 28 days, your ‘Ashtavakra quotient’ (AQ) is zero—0 AQ! On the two days when you do send over your question, then your AQ is maybe 0.1. For one or two hours of the day you decide to listen to me holding forth on Ashtavakra. All in all, what’s your net AQ across the month?

98% of your time you are choosing to be with the ones who are not with the One, mind you. And repeat it to yourself again and again and again. Look at the faces of your colleagues in the office—are they with the One? Then, why are you hobnobbing with them? Why are you breaking bread with them? What are these parties? What are these smiling exchanges? Are they with the One? Then, why are you with them? What crushing need compels you to sell your soul? I’m not insinuating, I’m asserting.

Go to your Facebook contacts, look at your LinkedIn contacts—who are they? Alright, here’s a check. When a new contact request comes to you, what do you check in the fellow’s profile? Do you check whether he is with the One? You don’t. You rather check whether he is going to be useful to you when you make the next job switch. Did you ever give this criterion even 5% weightage: how spiritual is the fellow? Before you accept somebody’s friend request, do you bother to inquire how deeply spiritual the fellow is?

Just as a college student doesn’t bother to check the ‘spiritual quotient’ (SQ) of a girl who makes a pass at him, an industry veteran doesn’t check the spiritual quotient of another professional who sends him a contact request. That’s too much to ask for and so impractical it sounds. You see, we are going to relate on a worldly plane. Why check each other’s SQ? Fine, don’t check that.

If you do not check the SQ of the people in your vicinity, then your world will remain a spiritless world, shorn of spirituality.

If you want to check how deeply spiritual you are, check the SQ of people in your vicinity. As they say, a man is known by his company.

Your SQ is the average SQ of all people in your contact list. It’s an identity. AP’s law—note it down.

Next law, more in the language of calculus: Your distance from the One will tend towards the distance of your nearest one from the One. So, if your distance from the One is five units, and your great friend's distance from the One is 200 units, then very soon your distance from the One will be 200 units. AP’s first and second laws—the third is coming!