Biography

एक कहानी शुरु होती है सूरज के ढलने के बाद, अंधेरा कितना घोर घना है जाना दीया बनने के बाद, आधी रात क्यों लौ जली थी जानोगे तुम भी जलने के बाद।

A story begins after the sun has set; how dark the night is - you’ll know when you’re lit. Why the flame burns on at midnight, you’ll know when you too burn bright. (English translation)

The Mission - Uncompromising Non-Duality

Humanity stands at a strange crossroads: outwardly accomplished yet inwardly restless. We have decoded the genome and mapped the stars, but remain strangers to ourselves.

Centuries ago, the sages of India named this inner blindness avidyā and offered Advaita Vedānta - the philosophy of non-duality - as its remedy. Adi Shankara turned that insight into a revolution of clarity, but over time ritual and organized belief buried its spirit of enquiry.

When even classical Advaita had to compromise - separating Paramārtha, the realm of truth, from Vyavahāra, the realm of social order, and allowing inner realisation to coexist with outer conformity, often treating social evils such as caste, patriarchy, or divisive nationalism as ordinary life - Acharya Prashant refused that divide. He insists the two must become one: any life where understanding does not transform the very centre of living is hypocrisy - from diet and career to politics, planetary responsibility, even religion itself.

Our modern and revered teachers, too, remained incomplete in their endeavour. Some diluted the truth to please the masses, some withdrew into silence while the world burned, others acted as activists without philosophical depth, and some rejected religion altogether. Acharya Prashant stands apart - the first to let philosophical depth and social courage meet as one.

He declares there is no such thing as “personal liberation.” True liberation and compassion must overflow beyond the individual, embracing all humans, animals, and the planet in its entirety.

He reclaims religion itself - entering its heart, cleansing it of dogma and superstition, and restoring it as a vehicle of liberation rather than bondage. He challenges Lokdharma - the social religion of blind faith - with unprecedented sharpness, while revealing the sacred essence beneath.

Acharya Prashant is not merely a philosopher or a public intellectual who passively accepts the world as it is. He refuses to believe that Paramārtha - the realm of truth - must ever be compromised to preserve the status quo.

He has not only brought the highest philosophical insights of Advaita Vedānta into practical life for those who seek it, but has also dared to bring this wisdom to those who resist it - something even Shri Krishna warned against in the Gita.

And not only did he dare, he succeeded.

Through social media, he reaches people with the lowest attention spans - through short reels and clips - quietly allowing the essence of Vedanta to seep into society.

For more than two decades, he has spoken to audiences worldwide, bringing uncompromising clarity to the dilemmas of modern life - through reason, humour, and relentless honesty.

Through digital media, his mission has become a global ecosystem of learning. Author of 160+ books, including over 20 national bestsellers, and followed by more than 90 million people across social platforms, he has used technology to bring timeless wisdom into everyday consciousness. At its heart lies the Gita Community - a vibrant space of live sessions, daily wisdom activities, regular examinations, and daily written reflections - now numbering over 100,000 members. Against the logic of online superficiality, he has built a digital movement that grows deeper, not merely wider.

By challenging ritualized religion, pop philosophy, market spirituality, and political identity alike, Acharya Prashant has become a quiet danger to power - religious, social, political, and economic. Yet he remains focused on his work, insisting he fights no one but falsehood.

This fusion of philosophical depth, fearlessness, and authenticity - realised on a scale never seen before and without surrendering an inch of integrity to popularity - makes him historically unique.

Roots of Rebellion

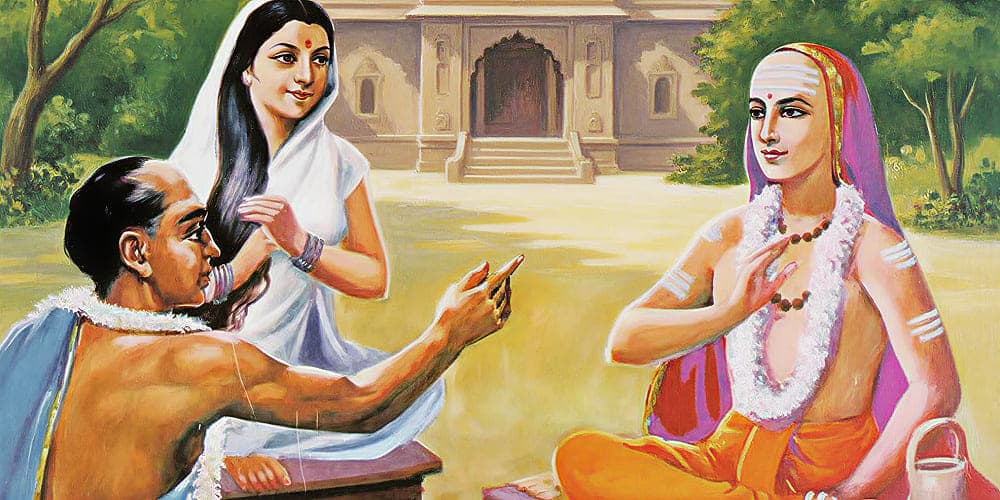

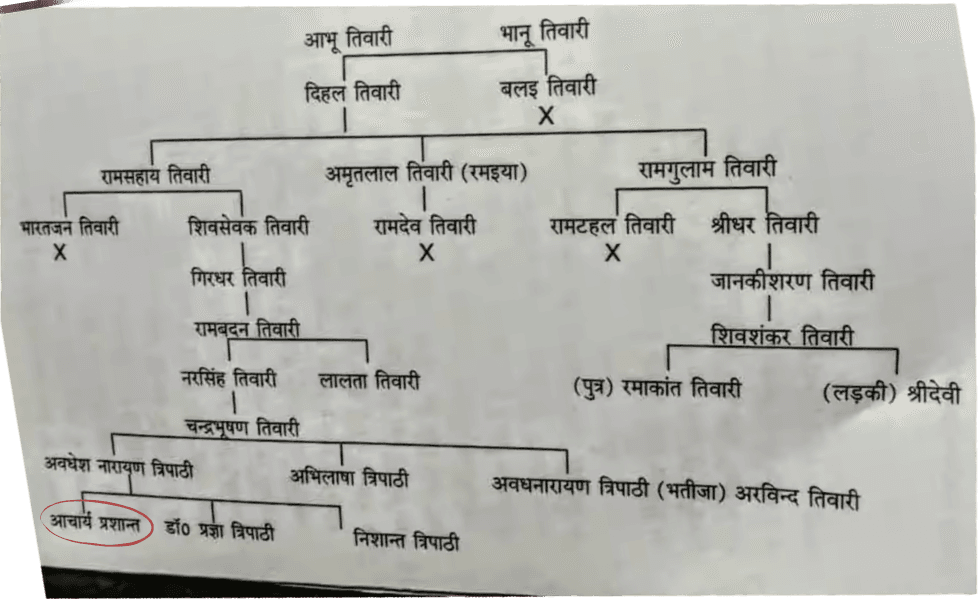

On his maternal side, Acharya Prashant's ancestry traces back to Mandana Mishra, the renowned scholar who was famously defeated in debate by Adi Shankaracharya.

The philosophical contest was high-stakes: the loser had to become the victor's disciple and adopt the life of a Sannyasin (renunciate). The judge was Mandana Mishra's brilliant wife, Ubhaya Bharati.

The debate centered on two core philosophies: Shankaracharya championed Advaita Vedanta (self-knowledge is the sole path to liberation), while Mishra defended Purva Mimamsa (ritual action is the path to liberation). Shankaracharya ultimately won the argument; and as tradition holds, Mandana Mishra accepted the defeat and became his disciple, taking the monastic name Sureśvaracharya.

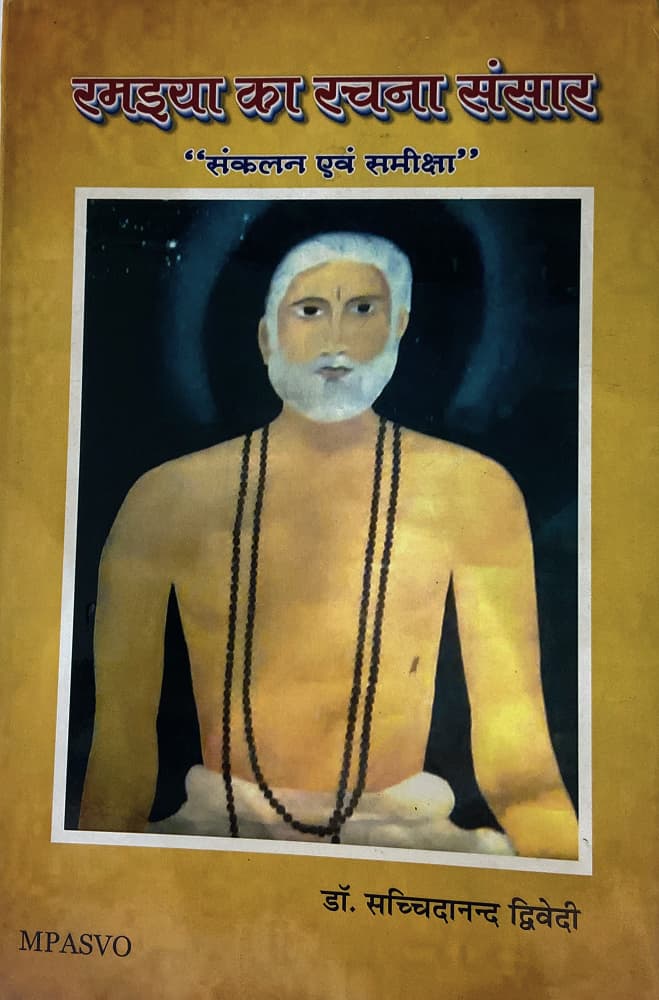

Among his more recent forebears was his great-grandfather - Ramaiya Baba - an eccentric Advaitic Aghori saint whose book of dohas is still known in the city. Revered by villagers, feared by pandits, and often abhorred by the orthodox.

One of the most striking episodes of his life involved the leading courtesan of Varanasi, who approached him seeking to “wash off her sins.” Instead of offering ritual absolution, he married her. The act scandalized society, and he was ostracized, but he embraced it with characteristic boldness. His verse captured the moment:

माया मेरे घर आई, मैने उसे बनाया लुगाई

He ate with those deemed untouchable, married outside caste boundaries, and openly confronted Vaishnav orthodoxy. He is remembered as a saint who angered many but could not be ignored.

A book of Ramaiya Baba’s verses, preserved by the family, includes a chart of his descendants. The last name recorded is that of Acharya Prashant.

It would have been easy to claim respectability through ancestry, but he chose otherwise. He broke away, refusing to be defined by inherited reverence, and carved out a path that was entirely his own.

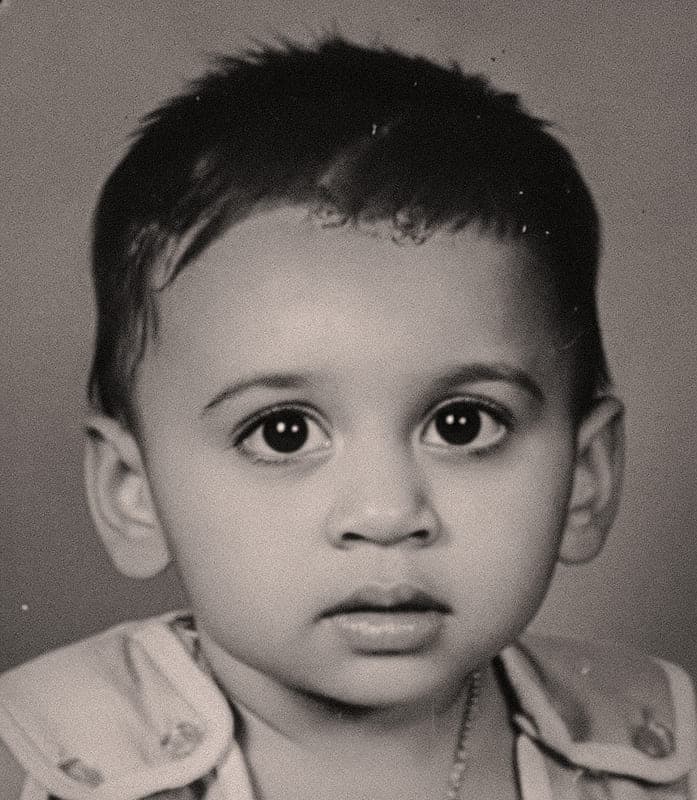

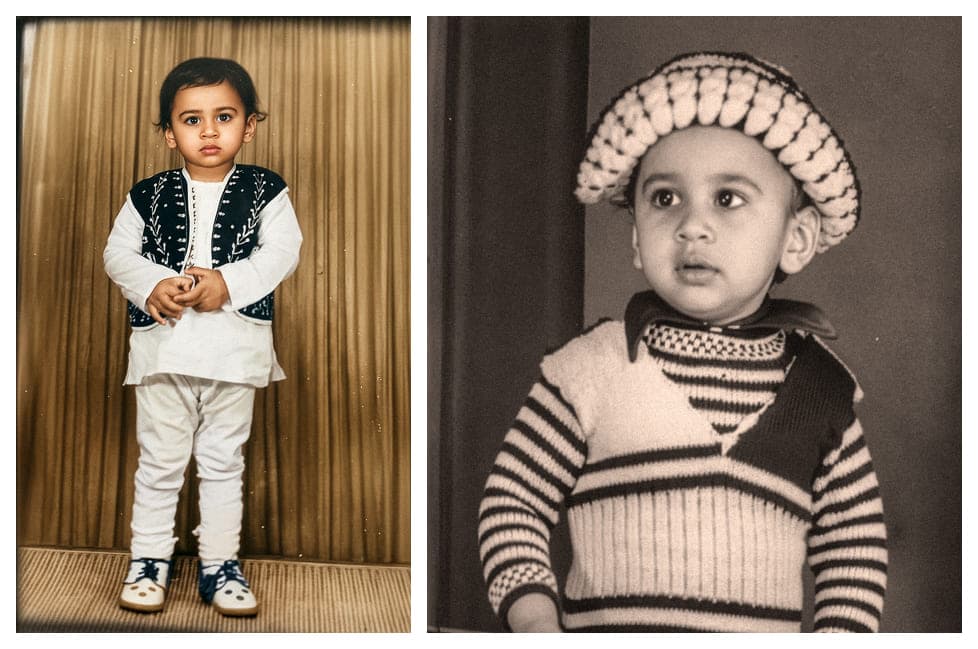

The Dawn (1978-1995)

It began with a child’s unease that something, somewhere, was terribly wrong.

Prashant Tripathi was born on 7 March 1978, on the sacred occasion of Mahashivratri, in Agra, India. His birth on a day devoted to Lord Shiva would later seem symbolic, but at the time it was simply the beginning of a life that would unfold with unusual intensity.

He had always been a keen observer ever since he was a child. What he observed behind the niceties of life was ignorance, discord, and sufferings that plague normal human life.

The future teacher hardly nurtured any ambitions or dreams to become something in the future. During his studies, he does not remember keeping any long-term objective, he says. He was just watching the world attentively, without coming to any quick conclusions.

“I don't remember feeling content with my understanding of life, nor do I remember having a plan for the future. I was not even actively thinking about changing the world. However, I was sure something was so excruciatingly wrong that it needed all my continuous attention to unravel it. Hence, I just dedicatedly kept trying to understand”, he says.

Prashant wasn't one to sweep things under the rug as he recalls, “I'd say things as I saw them and this allowed me to process things in a very raw manner. I did not pretend to understand if I did not. If something was beyond my comprehension, I'd let it stay because there was nothing I could do about it. And this process was continuous and laborious and required patience.”

“As a kid, all these sights were being registered and questioned by me. The ugliness was being disliked. There was a constant urge to change the shape of things,” he says.

Along with this sensitivity, he also developed a strong sense of responsibility at a very early age.

Living in Kanpur, when he was barely two-and-a-half years old, frequent power cuts were common. One summer evening, while his parents were on the rooftop, the electricity went out, and the fan in his room stopped. The little boy woke up, got off his bed, and set out - still in his shorts - to fetch an electrician from the market.

On the way, he met the neighborhood milkman, who asked where he was going. Calmly, he replied, “The electricity is out, I’m going to get the electrician.” Panic had already broken out at home, but by the time his family reached him, he had already asked the electrician to come. Reflecting on this incident, Prashant says it shows how, even as a toddler, he felt it was his duty to “bring light when there was darkness.”

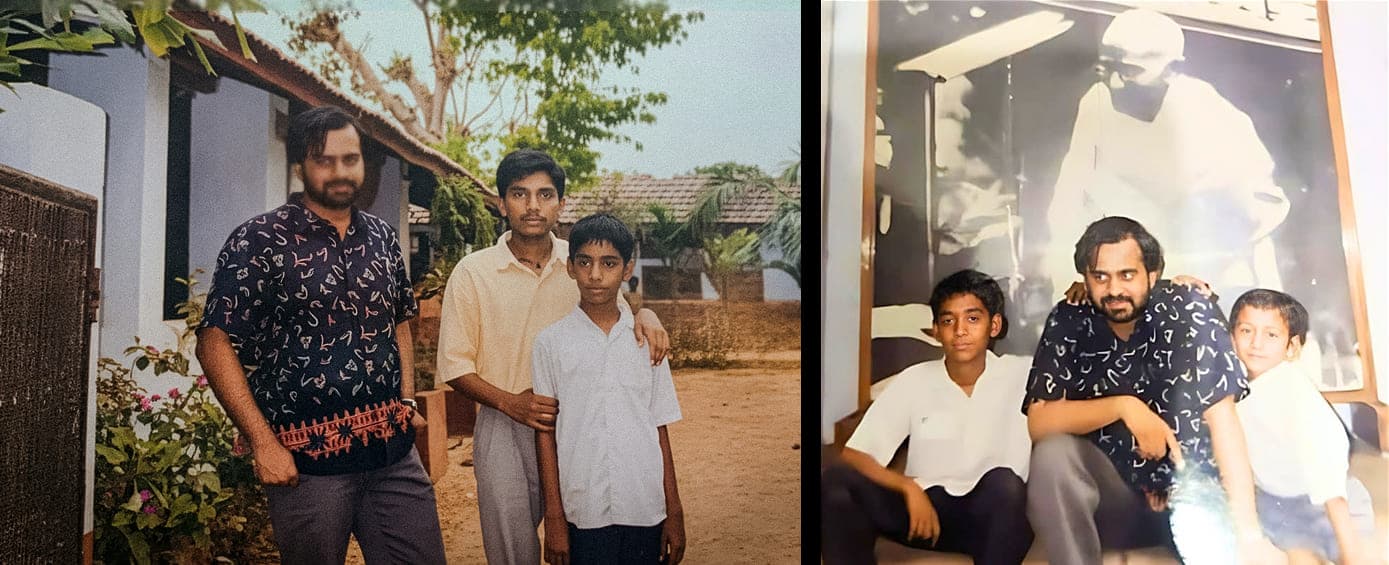

As a little boy, Prashant once travelled with his family to Maihar, a temple town in central India, for his younger sister's mundan - a traditional Hindu head-shaving ritual for young children.

She was just a year-and-a-half old, doll-like, with soft, beautiful hair, as he described. Excited, he thought a grand celebration was about to happen. But when the barber began shaving her head, she burst into tears. Seeing her cry, he too cried out, unable to bear it.

He turned to the women of the house and asked, “How would you feel if someone shaved your head?” The question shocked everyone. A slap silenced him, but only for a moment. Through his tears he kept asking, “Why are you doing this? Her hair was so nice. Is there any medical reason?”

Of course, there was none. Later he would recall, “They were just doing things without thinking.”

Even in childhood, his spirit was clear: wherever he saw falseness, he could not stay quiet. He had to question, to protest, to stand at the front against it.

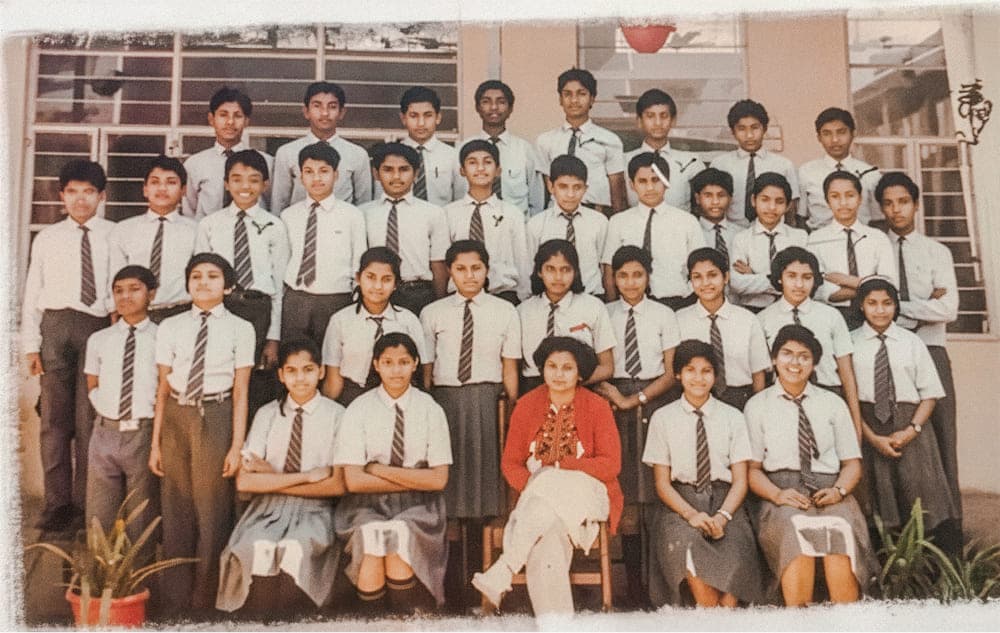

He was quite the reader, played a lot, was also known to have plenty of mischief, and this while being an introvert. Being good at studies seemed like a natural ability- he topped the ICSE exams, secured the first position on the inter-branch merit list, and was also an NTSE scholar.

After topping Class 10, he was felicitated on many occasions and received several gifts.

Two stood out - a moped from his maternal grandfather and an Atlas cycle from the then Governor of Uttar Pradesh, Shri Motilal Vora. When it came time to commute to school in Class 11, he chose the Governor’s cycle over the moped. To him, honor and dignity held far greater value than comfort and convenience. This remains true to this day.

In his school days, Prashant often found himself at the receiving end of strict discipline. Even when he became Head Boy in Class 11, the role earned him no special treatment. “Half the time I was standing outside the class in punishment,” he recalled. “The teachers never thought, ‘He is the Head Boy, let us spare him.’ In fact, I was punished more than others. Where an ordinary boy might be forgiven, I was sent out directly. No special status.”

One lesson that stayed with him for life came much earlier, in Class 5. Once, he had gone to school without doing his homework. The teacher asked him repeatedly: “Could not do it, or did not do it?” At first, the young boy was confused - unsure which of the two answers would be more shameful. But the persistence of the question drove the point home. “Not being able to do something, and simply not doing it - these are two very different matters. That clarity struck me that day, and I am grateful for it.”

Another turning point came when he moved to a new school in Ghaziabad after his Class 10 success. In his very first exam there, he misread the date sheet and arrived late. The principal refused to let him write the paper. “He said, ‘It won’t harm you to miss one paper, but if I allow you, you’ll pick up the wrong habit.’ Imagine - having just topped the state, and the very first exam in the new school I was marked failed.” “They gave me no concessions,” he recalled. “Not a single percent of leniency. And I am deeply grateful. It kept me steady, kept me humble.”

What distinguished his childhood was his proclivity to read books of all types beyond his syllabus.

“Reading wasn't confined to one particular genre. I was hungry and absorbed whatever came my way. From comics to somebody's PhD thesis, even if I couldn't make much of it,” he recalls. He feels that this is what made him mentally branch out erratically in all directions with no particular plan or pattern. This aided him to grow organically, without a blueprint.

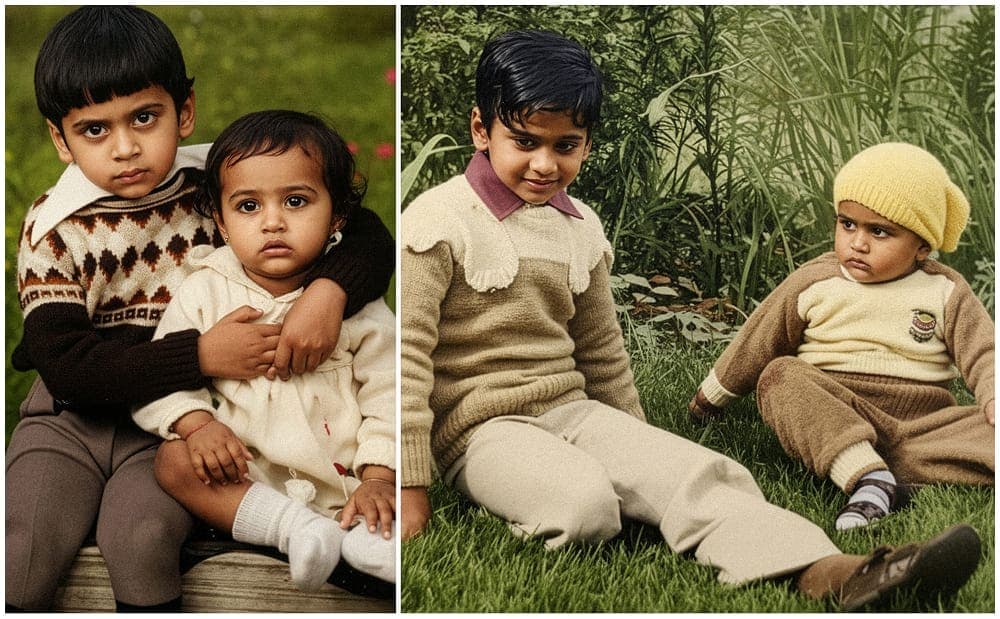

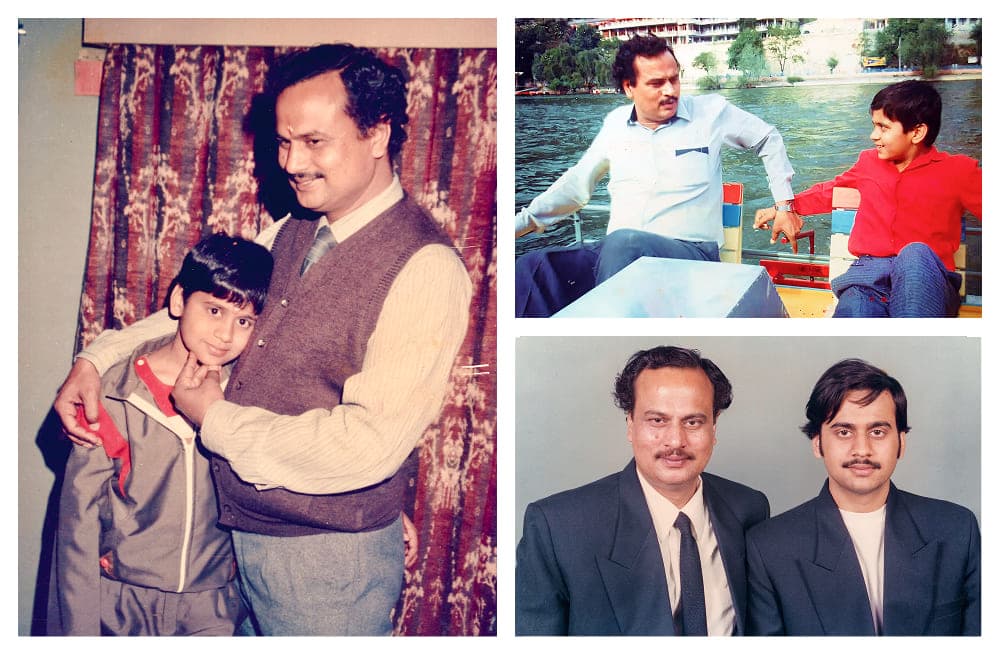

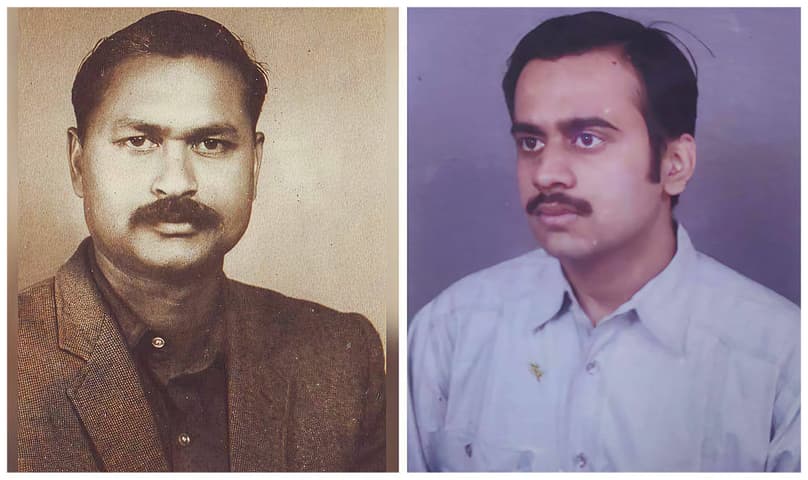

Prashant's connection with his father was special, to say the least.

Prashant’s father, Shri Awadhesh Narayan Tripathi Ji, was a man of remarkable clarity: a problem that would take Prashant ten minutes to explain would receive a solution in half a minute, stripped of all complication.

From him, the boy learned the value of silence - speak only when words add more than silence can - and a rare kind of sensitivity that was never sentimental. “He was deeply sensitive,” Prashant said, “but I never saw him being overly emotional. Otherwise, he could never have written the poems he did.”

His father left a quiet but indelible mark on his upbringing. A government officer by profession and a well-read man by temperament, he filled the family home with books that far exceeded the narrow syllabus of school. Shelves overflowed with history, politics, science, poetry, and philosophy, creating an atmosphere where serious thought was part of daily life.

When his job postings took the family to small towns like Shahjahanpur, where there were no real bookstores, he would plan trips to Lucknow with a special purpose: to buy books for his son. “I'd never be satisfied with the collection I had,” Prashant later recalled. “So my father would take me to bigger cities to purchase books. It was remarkable to travel just to visit a bookstore.” These journeys, and the treasure they brought home, became his greatest delight. In later years he would say those books acted as insulation, protecting his mind from the “filth and dirt” of the world, surrounding him instead with noble voices that left no room for trivial distractions.

But his father’s influence reached far beyond books. What left the deepest impression was his uncompromising honesty. Prashant saw, time and again, how his father would refuse to bend before superiors. Promotions were often delayed for years, forcing him to go to the High Court to secure what was rightfully his. The cost was real: he eventually retired at a position lower than he deserved. Yet never once did he barter truth for comfort. As a boy of eleven, Prashant watched his father publicly correct the Chief Minister of Uttar Pradesh, Narayan Dutt Tiwari, on stage before a thousand people. It was a moment that etched itself into his memory—truth spoken plainly, without fear of consequence.

Looking back, Acharya Prashant often said that what he received from his father - books, courage, silence, and sensitivity - were the best gifts any child could hope for. These early influences became the foundation of his inner life, preparing him for the struggles, clarity, and uncompromising truthfulness that would later define his own mission.

If his father shaped his intellect and clarity, it was his mother who built his resilience.

At home, weaknesses and indulgences found no shelter. If he stumbled or failed, there was no pampering, not even consolation - the unspoken lesson was simple: get up and move on.

This discipline showed itself in unforgettable ways. Even when feverish, he was expected to cycle to school for exams. The message was clear: comfort and illness mattered less than commitment to one’s duty. Yet this strictness was never neglect. It was, as he would later say, a “soldier-like” preparation for life. Outward affection was rare, but quiet care was always present - like the glass of milk his mother would press into his hands each morning, even when he was sixteen and nearly grown.

Her discipline extended to herself as well. After a serious car accident that left her hand injured and his father disfigured, the parents concealed their suffering for ten full days, waiting until his UPSC interview was over before telling him. It was a striking example of the same principle they had lived by in raising him: no weakness, no distraction, even in the face of personal pain.

Together, his parents fostered a style of parenting that valued honesty, courage, and self-reliance above everything else. Overt pampering was absent, but love was present in subtler, deeper ways - in the books they brought him, in the discipline they demanded, and in the sacrifices they quietly made so he could walk his own path.

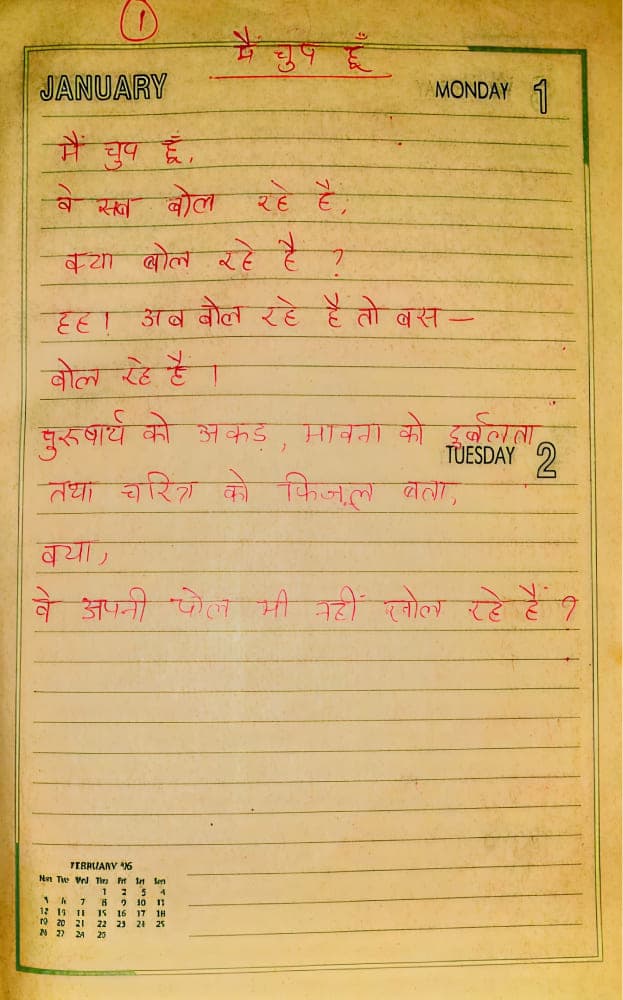

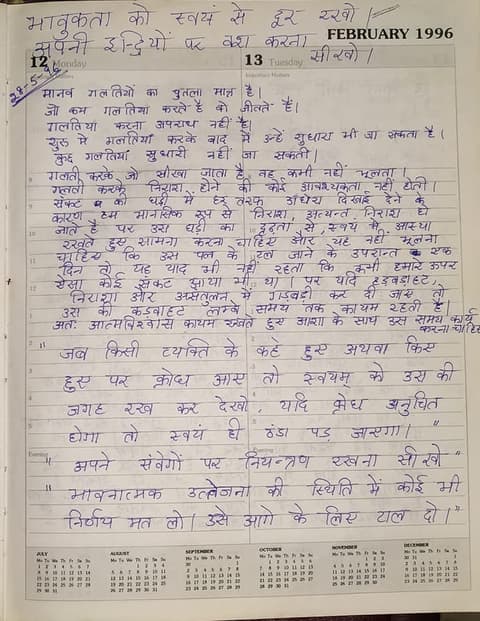

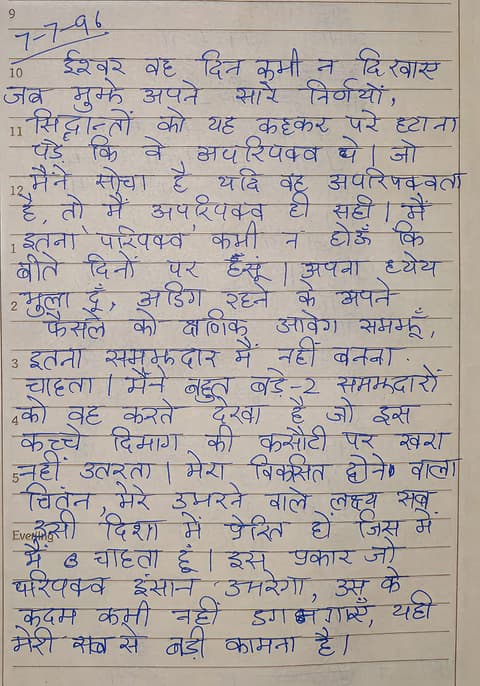

By the mid-1990s, while still in school, Prashant had already begun giving shape to his inner restlessness through words. In 1995, he wrote a short poem that captures the sharpness of his gaze at a young age:

मैं चुप हूँ, वे सब बोल रहे हैं; क्या बोल रहे हैं? हह! अब बोल रहे हैं तो बस — बोल रहे हैं। पुरुषार्थ को अकड़, भावना को दुर्बलता तथा चरित्र को फिजूल बता, क्या, वे अपनी पोल भी नहीं खोल रहे हैं? ~ प्रशांत, 1995

I am silent. They are all speaking— but what are they really saying? Ah! Now that they speak, they merely speak. They call effort arrogance, emotion weakness, and character futile. Do they not see— in saying so, they only reveal themselves? ~ Prashant, 1995

It is the voice of a teenager, yet already cutting through pretension and exposing the falseness in society’s values. The clarity that would later define Acharya Prashant was not a sudden arrival; even in adolescence, it was beginning to find its expression.

Prestige and Protest (1995-2003)

In the corridors of success, a quiet rebellion was taking shape.

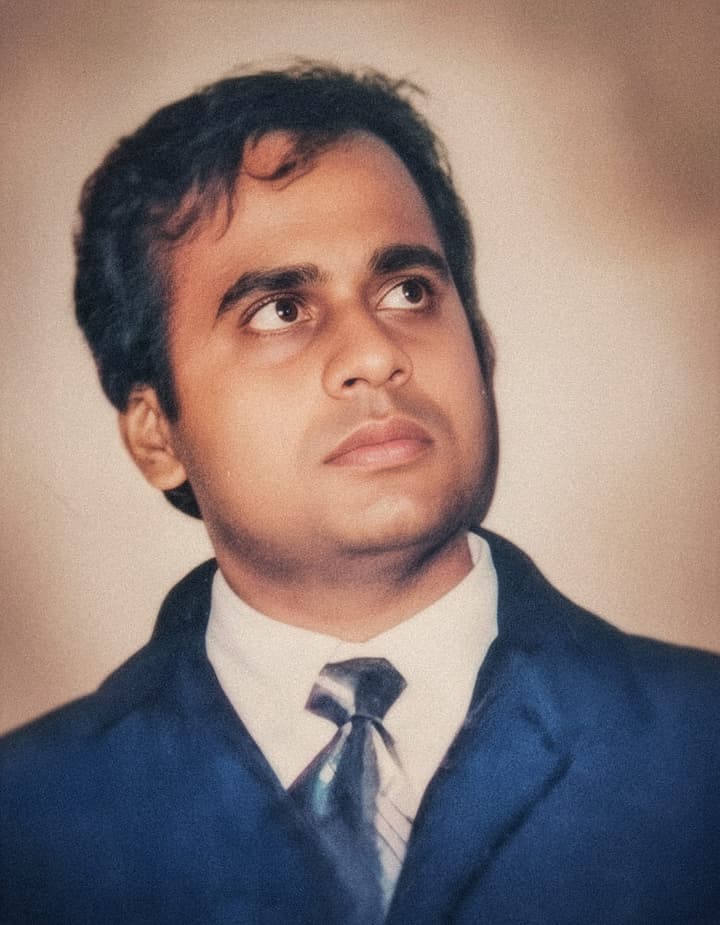

These were the years when Prashant entered India’s most coveted institutions—IIT Delhi and later IIM Ahmedabad - symbols of success for an entire generation. Yet, while most celebrated the prestige, he was already questioning its very foundations. What others saw as triumph, he experienced as a burden. Poetry, theatre, and inner rebellion ran parallel to the glitter of degrees.

At IIT, the literature of Dhoomil hit him like a storm, igniting a fire of dissent that words alone could barely contain. At IIM, he staged plays that shook audiences and turned interviews into confrontations with the corporate machine. To his peers, these years promised careers of comfort and recognition; to him, they revealed the hollowness of ambition.

It was a time when he bore the crown of prestige on his head, but in his heart carried protest - a protest that would only grow louder with each passing year.

IIT Delhi

Prashant grew up in a family where the Indian Civil Services - elite government roles seen as a direct path to social impact - were held in high regard. In India, entry into these positions comes through the highly competitive national examination conducted by the Union Public Service Commission (UPSC).

His decision to study at the Indian Institute of Technology Delhi (IIT-D), one of the country’s most prestigious universities, was less about engineering itself and more a strategic step: many top UPSC candidates came from IIT backgrounds.

Dhoomil

Sudama Pandey, known by his pen name Dhoomil (9 November 1936 – 10 February 1975), was a Hindi poet whose work came to embody the spirit of protest-poetry in modern Indian literature. His writings were marked by defiance, urgency, and a sharp critique of social and political hypocrisy.

At IIT-Delhi, Dhoomil entered Prashant's life when he was 18 years old.

He describes the impact of reading Dhoomil at age 18 as an “electric current” passing through him, and he feels that either Dhoomil's words are timeless, or he himself hasn't grown beyond that 18-year-old self.

“I just grew up. Rather, I exploded into maturity upon meeting him.”

At 18, while studying at IIT, one of Prashant's articles in the IIT's magazine caught the attention of an AIIMS cultural festival head. Impressed, he sought Prashant out and invited him to participate in their events - Pulse, where he participated in poetry, debating, sports, and other activities. It was through him that Prashant was introduced to some noted poets - most memorably, to Sudama Pandey 'Dhoomil'.

Within one semester of encountering Dhoomil, Prashant wrote Dhoomil's lines (and others' quotes) all over the walls of his hostel room, which made many people hesitant to enter, feeling overwhelmed by the “heavy” words.

Prashant admits that “a lot of what he [Dhoomil] was saying, I knew, but he presented it as a testimony”, affirming his own understanding and encouraging him to speak the truth without fear.

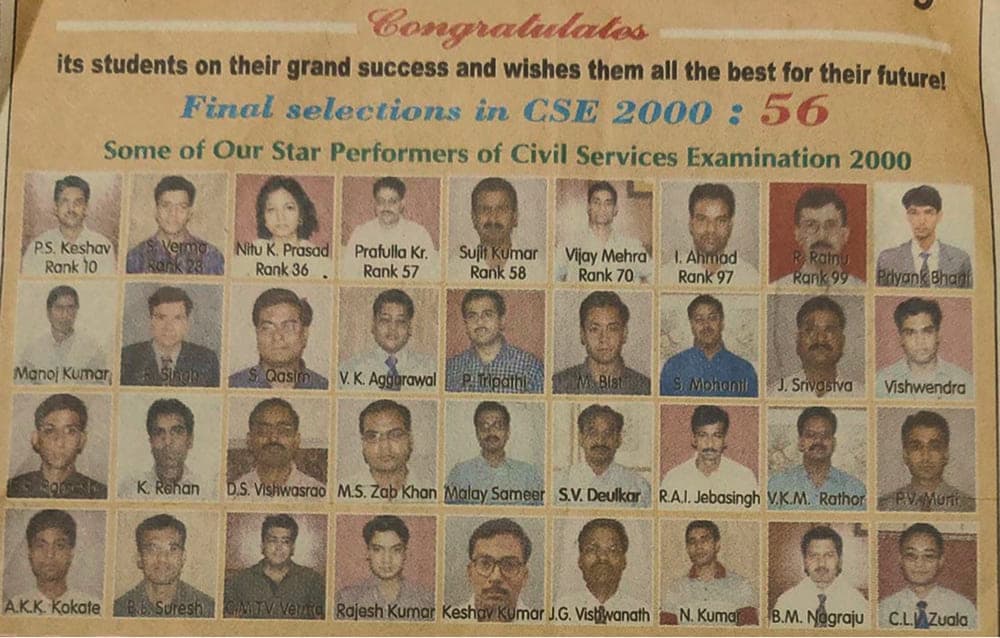

UPSC Interview

“Between IIT and IIM lay a decisive interlude: the civil services.”

Preparing for UPSC drew him deeper into India, the world, the Constitution, and current affairs. For a time he was certain: “IAS is the route; the world’s picture must change.”

But as preparation matured, something in him shifted. “By the time the interview call came, I had grown indifferent to the civil services.” He doubted whether radical change could be enacted from within bureaucracy. The long-awaited moment felt almost anti-climactic.

He arrived on his motorbike - white shirt, jeans, no tie. “Why the pretence? If jeans are fine otherwise, why change for this?” In the waiting room, few didn’t even realize he was a candidate. Inside, the panel of six to eight didn’t mention his attire. Instead, they went long and deep - politics, the economy, science, history. Because his application form mentioned poetry, they asked, “Would you recite some of your poems?” After a gentle nudge, he did.

The conversation ran unusually long - close to an hour - and the result startled even him: “I scored 210 out of 300 in the interview.” He felt the board had understood his mind and, “with a certain graciousness, told me they would have liked to see me in the IAS.” The experience, he later said, “raised my respect for UPSC; perhaps I was fortunate to face a truly perceptive panel.”

He often reflected on his approach to interviews of every kind - civil services, campus placements, or corporate panels. “Every interview is a kind of power play,” he said. “The person across the table sits there with the belief that he has authority - rank, position, the upper hand. And that’s exactly when I feel like confronting them.”

For him, interviews were never formalities or performances - they were honest encounters. “My interviews were always spicy,” he laughed. “And yes, I paid the price for that. But what’s the point of sitting quietly when the situation itself demands rebellion?”

IIM Ahmedabad

“I actually wept on the day I reached the campus because I had never wanted to be there.”

The civil services had always remained an open door. Having cleared the UPSC prelims, he still had attempts left. “My past was calling me to the academy… I could have appeared another time and gotten into IAS proper. It was very feasible; I just had to improve my rank a bit,” he remembered. Yet another part of him pulled away. Reason told him that the bureaucracy was not the place for the kind of change he sought.

“I didn’t want management or cosmetic changes, I wanted to upend it all. I wanted a very shift of the centre the entire world operates from. Nothing short of a revolution would suffice. And the bureaucracy is not the place where revolutionaries can do their work.” With a heavy heart, he let go of his IAS dream.

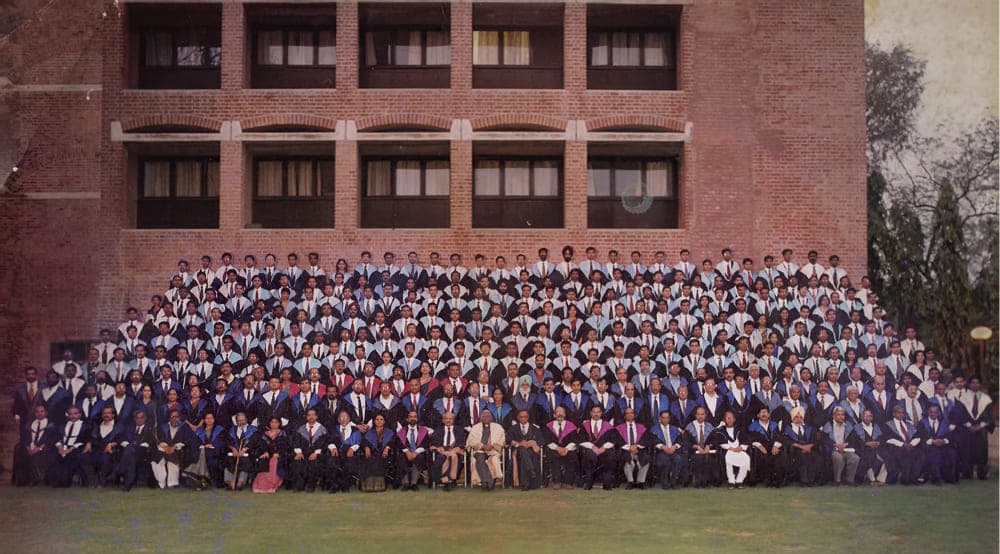

Following the CAT, Prashant secured admission to all three premier IIMs - Ahmedabad, Bangalore, and Calcutta - a rare feat that placed him among the most distinguished candidates in the country. He ultimately chose to pursue his studies at IIM Ahmedabad.

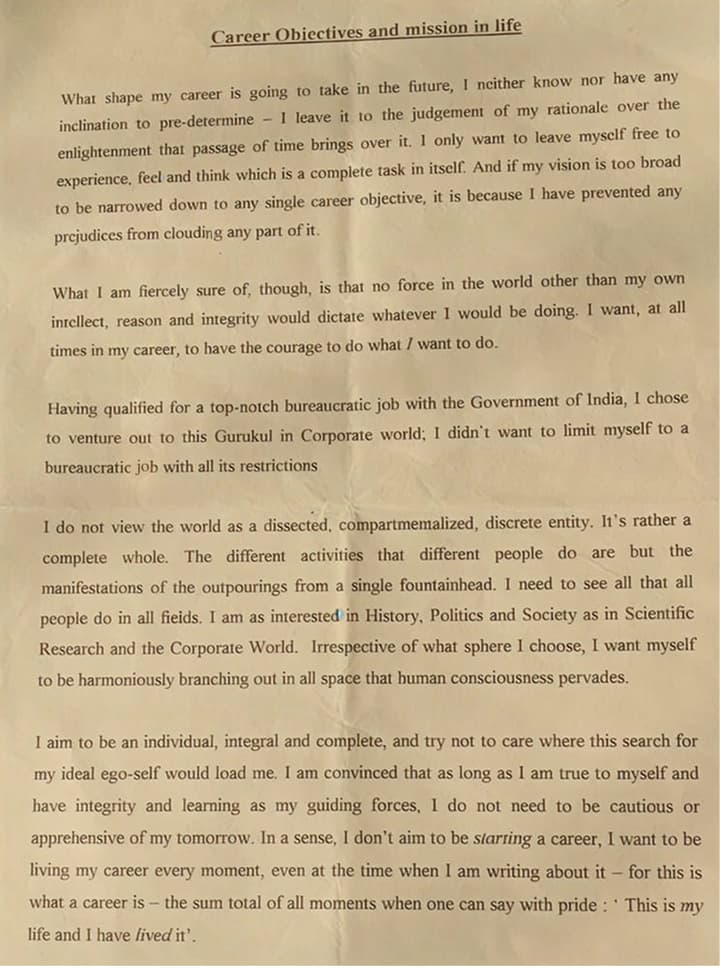

During his years at IIM Ahmedabad, Prashant was selected to apply for the prestigious Aditya Birla Scholarship - a fellowship open only to the top performers of the CAT examination across all IIMs. As part of the process, he was required to submit an essay describing his career vision.

What emerged was not a conventional career plan but a declaration of inner freedom.

“What shape my career is going to take in the future, I neither know nor have any inclination to pre-determine.” he wrote. “I only want to leave myself free to experience, feel and think which is a complete task in itself.”

He refused to treat career as a linear pursuit of success or specialization. “If my vision appears too broad to be narrowed down to any single career objective,” he continued, “it is because I have prevented any prejudices from clouding any part of it.”

The essay revealed the same clarity that later defined his teaching: an insistence that action must arise from understanding, not ambition. “No force in the world other than my own intellect, reason, and integrity would dictate whatever I would be doing,” he wrote. “I want, at all times in my career, to have the courage to do what I want to do.”

By that time, he had already qualified for a top bureaucratic post with the Government of India but had chosen to turn toward the corporate world—only to find even that too confining. “I did not want to limit myself to a bureaucratic job,” he explained, for the world is not a set of divided compartments. Science, politics, art, and business are all expressions of one centre of human consciousness. He concluded the essay with a statement that now reads almost prophetic:

“I don't aim to be starting my career, I want to be living my career every moment, even at the time when I am writing about it - for this is what a career is - the sum total of all moments when one can say with pride : This is my life and I have lived it.”

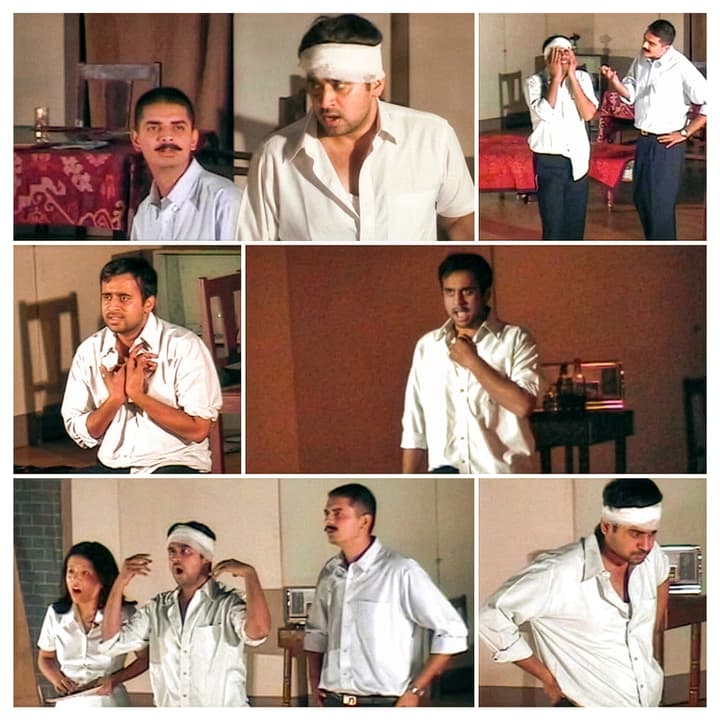

At IIM, his restlessness soon found a different outlet. In his second year, he discovered theatre and gave himself fully to it.

He joined the dramatics society IIMACTs, staging works of Ayn Rand, Eugène Ionesco, Badal Sarkar, and Mohan Rakesh. “All my angst got expressed on the stage itself. Those plays were an expression of what I was going through.”

One production in particular, Ionesco’s Rhinoceros, became a sensation in Ahmedabad’s student and intellectual circuit. Tickets were priced higher than those of MICA, which regularly featured NSD actors, yet the shows were packed. The play raised over ₹5 lakhs in ticket sales and another ₹6.5 lakhs in sponsorships from corporate brands. Even MICA’s own theatre team came forward in admiration.

What lay behind the success was not professional polish but an uncommon spirit. None of his peers had acted before, but under his direction they matched, and often surpassed, experienced groups. Sets were changed in seconds through innovative rolling backdrops. Rehearsals began at 8 p.m. and continued until dawn, despite the academic pressures of IIM.

The bond was so deep that even batch toppers addressed him with unusual reverence as “Director Sahab” and “Aap” - a sharp contrast to the casual slang of campus culture. The devotion of his peers bordered on extraordinary. Handling logistics, sponsorships, direction, and his own lead role, there was always the chance he might miss a line. To safeguard him, the team memorized not only their own dialogues but his as well, ready to prompt him at the slightest slip.

The intensity of his commitment spilled into daily life. To fit a role, he would do push-ups during rehearsals, having no time to go to the gym. Professors suggested he consider acting or directing professionally. Once, after a play, he had to rush straight to a placement interview without changing; while the other candidates sat in formal suits, he walked in still wearing his stage costume.

Other productions followed - Pagla Ghoda and Night of January 16th - where he played two starkly different central roles at the same time. His seamless performance drew such attention that an NSD (National School of Drama) director sought him out at his dorm at six in the morning to congratulate him personally.

By then, Prashant was not just known within IIM but across Ahmedabad. Students from other colleges came to campus simply to see the man who had taken the stage by storm.

He had become a star, though not in the conventional corporate sense. His theatre years at IIM stand as a vivid expression of his inner turbulence, his creativity, and his refusal to confine himself to the narrow expectations of management education.

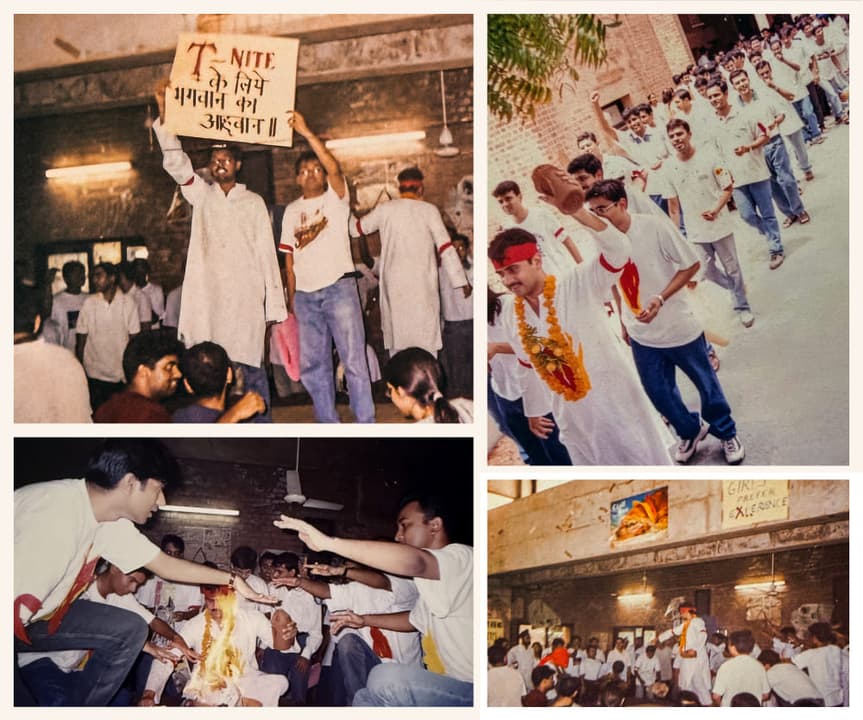

One of the posters in the image says “T Nite”.

This was the Talent Night at IIM.

Prashant wrote the script and played a cunning baba who fooled the sharp Wall Street executives by making them perform hawan (a traditional Indian fire ritual) and other rituals.

The baba led the procession, followed by the entire batch of 180 students - symbolizing how even the highest IIM IQ is no match for inner ignorance.

The procession moved through the entire campus, mocking the IIM framework itself.

Unlike most of his peers at IIM Ahmedabad, Prashant spent much of his time outside the campus in unexpected places.

“Nobody enters IIMs, especially in Ahmedabad, to do plays, and I was doing plays all the time. Nobody goes there to be sitting at the Gandhi Ashram half the time, and that’s what I was doing,” he later recalled.

The Gandhi Ashram at Sabarmati was far from the Vastrapur campus, yet he would regularly ride there on his bike. There he connected with an NGO named Manav Rachna, working with underprivileged children - teaching them, distributing supplies, and spending time with them. To support this effort, he found ways to earn and contribute whatever he could.

Placement season at IIM Ahmedabad brought Prashant face-to-face with the corporate world - a world that left him unmoved.

He often recalled walking into interview rooms with an irrepressible air: “I would enter sometimes purposefully with a swag - not always purposefully, but it used to be there. I couldn’t help it. I would look at that HR panel, and what could I do? It evoked no respect at all. I would look at them as corporate mercenaries, hired slaves.”

In one such interview, an HR professional asked him, “Convince me that you will be with us one year down the line.” His reply was characteristic: “Ma’am, will you be there one year later to check this thing out?”

Another incident came during rehearsals for a play he was directing and acting in - the role of a drunkard mourning his beloved at a crematorium. He was so engrossed in the rehearsal that he forgot about a scheduled interview. Dressed in shabby clothes, with disheveled hair, he was told the panel was waiting. “I thought, I don’t have the time to change, and I don’t even intend to change. So I went straight to the interview in that get-up.”

What followed was not an interview but a two-hour conversation, stretching far beyond the typical 20-minute slot. Both sides knew no job offer would come of it. Yet, the dialogue left its mark. At the end, the panel concluded, “Of course, you would have understood that this job is not for you.”

Prashant agreed - but added his own challenge: “May I also say something? It’s not just that I should not be in this job - even you should not be in this job.” He pressed them further: “When you were 15 or 20 years of age, if someone had told you that you would spend your entire life selling washing powder, would you have accepted that deal?” The interviewers fell silent, eventually admitting, “No.”

He continued, “Then why are you doing it now? Yes, selling washing powder fetches you a lot of money. I understand if you have a critical need for money - then for a short while you can take up this kind of job. Even I remained in three or four jobs, each for just a few months or at most a year, because I needed money to settle my debts. That is understandable. But now I see you are 40 or 50 years of age, and you are still here, continuing in this, and even building a career out of it. What kind of career are you talking about? You have simply grown accustomed to this life. If you could detach yourself for a while, you would actually feel disgusted. Detachment will bring disgust. You would be offended at what you have brought yourself to.”

For him, these interviews were not about securing jobs - they were encounters that revealed the emptiness of the corporate machine and gave him a chance to voice what he saw as its core hollowness.

He later recalled a quiet moment with his father on the day he left IIM after graduation.

“It was March 2003. I had packed up my belongings - my bedding, everything - and boarded the Ashram Express to Delhi. My father came to receive me at the station. I still had the government job in hand, and now, after IIM, the corporate offers too. Both doors were open - bureaucracy and corporate.

We sat in the car, both silent. He was by the window on one side, I on the other. For nearly half an hour, not a word was spoken. Then I said, ‘Papa, I’m quitting.’ No preface, no context - nothing. I didn’t even specify what I was quitting - job, career, world, everything.

He didn’t ask either. He just said softly, ‘All right then, quit.’

People later asked, ‘What were your parents’ reaction when you left UPSC?’ I could never explain. That was their entire reaction—simple, quiet acceptance. And maybe they already knew. A question that rises after so much silence often carries its own answer. He understood that the decision had already been made. There was no need for advice.”

Looking back, he would say that his father’s stillness that day was the purest guidance one could give.

“Perhaps I grew up because no one ever tried to make me grow up,” he reflected. “Had anyone forced me, I might have remained small.”

The Free Man in March (2003-2006)

Every paycheck was a step toward freedom. By March 2006, he walked out - a free man.

Prashant deliberately entered the corporate world with a clear objective: to clear his debts and buy himself freedom.

He switched industries frequently, not to build a career, but to learn widely and earn what was necessary. During this time, he tracked his expenses with precision, even maintaining an Excel sheet to calculate the exact month when his obligations would be over.

But while weekdays were spent at the office, his weekends belonged to something else entirely. “I picked up books that I especially loved, and figured out how they could be used to deliver leadership concepts. I devised a course, ‘Perspective in Leadership through Literature,’ blending wisdom literature with leadership education, and proposed it to a few management institutes. I would teach the same on weekends.”

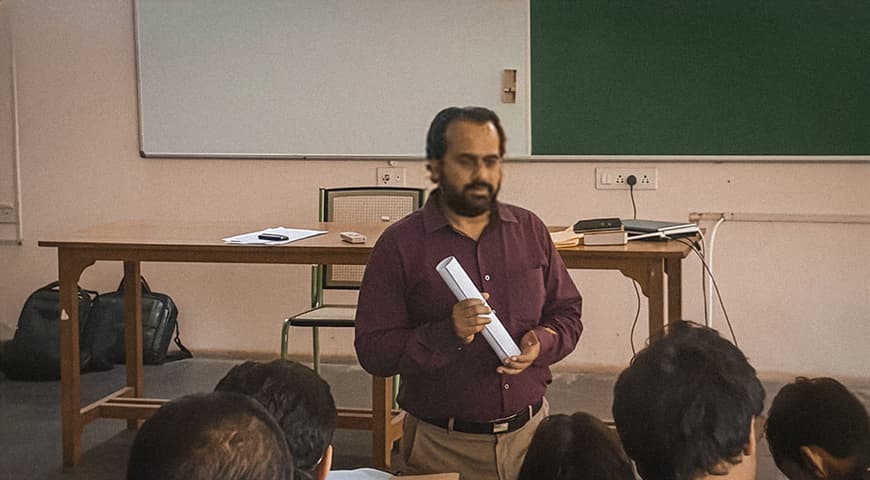

Soon, his weekends were busier than his weekdays. He traveled to IIT Delhi, Tata Institute of Social Sciences, Symbiosis, and the Institute of Management Technology - sometimes to multiple cities in a week - to engage with students. “One of my student batches was from Executive Management - all with more than five years of corporate experience - and I found I was younger than my youngest student in that class,” he remembered with a laugh.

What he was teaching was unusual for a management classroom. “Management education is mostly about finance, marketing, supply chain, recruitment - all things that concern external objects. There is not much in this education that takes you within. And unless you know where your desires, hopes, and motives are coming from, you will suffer, and you will make the entire planet suffer with you. Knowledge of the self must be the first thing.”

For him, these classrooms became laboratories of inquiry: “I was seeing, I was teaching, I was learning. Something was taking shape within. I was beginning to realise the origin of human bondage. I was seeing for myself where all the suffering comes from. In my classrooms, I was practically conducting experiments on how the monster of misplaced confidence and ignorant ambition could be fought.”

All through his corporate years, he maintained a meticulously prepared Excel sheet, which he had titled 'Free Man in March.'

It tracked every rupee of repayment, projecting the exact month he would be free of debt. By March 2006, the sheet’s forecast came true - he paid the final installment. “I knew exactly the month I’d be free. I had it on an Excel sheet. March came, the dues were cleared, and I walked out.”

That moment marked the end of his corporate journey and the beginning of a new chapter. From then on, he considered himself free of worldly compulsions, ready to devote himself entirely to the work that had already begun to take shape in those weekend classrooms.

When asked about marriage, Prashant is forthright:

“I didn’t want to be the typical husband. This institution of marriage — that irreversibly puts a man and a woman together with social sanction — was totally unacceptable to me. Being with someone is a very intimate thing. It has to do with the core of your individuality. And I just could not allow it to become a social institution, something that required legal sanction. So, I was out of it.”

Looking back at his college days, he shares his experiences with characteristic honesty. “Like any boy, I had my attractions. But I didn’t find too many worth it. I never found any woman spiritually worthy in that sense.” He recalls a few “innocent ones” who would listen to him, “but even their listening stops after a point.” The realization followed: “The one worthy of being loved is actually someone you will have to create.”

He often observed that girls “looked good from a distance.” But as he put it, “When I went near them, sat, caught, and talked — the game was over. They stopped being attractive.” In his IIT batch there were barely “one or two girls,” but he met others at inter-college events. Even then, if he spoke “plain and simple” things, they would sometimes “take offense.” “If my ordinary talk upset them, I would lose interest,” he said.

One incident stayed with him. A girl was dancing, and he joined in. She gave him a compliment, but he noticed, as he put it, “She was making a lot of faces while dancing.” He told her directly: “You make a lot of faces.” It was not meant as a taunt, but an observation. She took offense and walked away. “Such things kept happening,” he laughs, remembering how his blunt honesty often cut short potential attractions.

His critique of conventional love goes deeper: “Two unconscious people bumping into each other - that’s not love. That’s just a biological mandate. What the world calls love is often just a lifelong mutually exploitative relationship.”

For him, love and wisdom cannot be separated: “When people are wise, that’s the only time they can be in love. Without knowing yourself, you remain fundamentally incapable of loving anything.” His own work, he says, is an “exercise in love,” made available to all seekers.

Lighting Lamps in the Wilderness (2006-2015)

From classrooms to mountaintops - years of tireless travel and teaching.

After leaving the corporate world in 2006, Prashant founded Advait Life-Education, giving his insights and teaching efforts an organizational structure.

The centerpiece of the initiative was a long-duration program for students, later renamed the Holistic Individual Development Program (HIDP). It was aimed primarily at school, undergraduate, and postgraduate students - over 90 percent of them from engineering backgrounds. The HIDP combined experiential activities inspired by classical wisdom literature with modern management principles to foster personal insight and self-awareness.

“The HIDP was a work in progress, and every semester new activities would be drawn, and I designed them individually. This part was very personal to me,” he recalled.

Within two years, Advait Life-Education had recruited around 100 instructors and delivered the HIDP to more than 20,000 students across over 50 institutes nationwide. Demand was high - eager institutions lined up to host the program, and within academic circles HIDP had already created a buzz. Success had arrived early, and in the field of meaningful work.

By 2008, on turning 30, Prashant shifted the HIDP's emphasis from leadership training toward deeper spiritual engagement.

He introduced large-scale dialectical seminars under the banner “Samvaad”, and launched thematic modules such as “Kabir on Campus”, based on the poetry of Kabir Saheb, and “So Said the Sages”, drawn from the Upanishads.

As expected, this shift provoked resistance from all sides - host institutions, parents, students, and even his own faculty team. The questions were relentless: Would HIDP improve students’ careers? Would it help their grades? Prashant later remarked, “Still, they couldn’t dismiss what I was doing, because those who remained in my process saw tangible benefits within a semester.” With each passing year, the HIDP grew more stringently focused on self-awareness, and with that, the resistance only intensified.

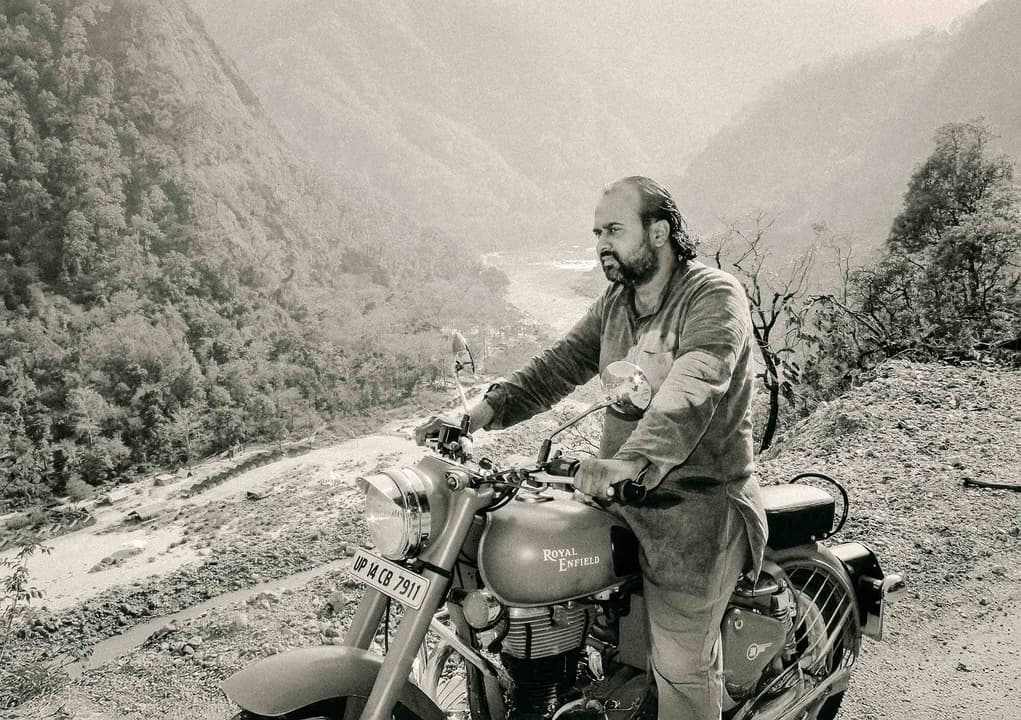

In 2010, at the age of 32, he conducted his first Himalayan Self-Awareness Camp.

Small groups of 20-50 seekers would travel with him to remote, serene locations in the Himalayas for retreats lasting from three days to a week. These camps became tools of deep personal transformation, drawing participants not only from across India but eventually from abroad as well.

Those who met him at these camps were often struck by the contrast: an extraordinarily meditative, radiant presence, so different from the humdrum of ordinary life. The everyday “Sir” soon felt inadequate to describe him. Nobody quite recalls who first suggested it, but a new honorific appeared and stayed: “Acharya” had arrived.

The Wilderness

By 2010, Advait Life-Education expanded rapidly.

Acharya Prashant realized that his faculty was struggling to deliver the HIDP programs with the depth and rigor he expected. “And then I saw that my faculty was not able to manage. So I took an extreme step. I said, I will do it myself.”

He created a demanding routine for himself: six days a week, conducting two sessions daily, each lasting two hours, in colleges across India. The program was no longer confined to one region - it was spread across five or six states, in 10 to 15 different cities. For several years, from 2010 to 2015, he lived almost entirely on the move.

His schedule was relentless. Each morning from 10 a.m. to 12 p.m., he would address a batch of 200 to 500 students. By afternoon, from 2 p.m. to 4 p.m., he would deliver another session to a second batch. The next day he would be in a new city - sometimes traveling overnight by car, train, or flight, and at times even by bus to reach remote campuses where no train line existed. “There were many times I would be asleep in the car, and just two minutes before the session someone would wake me up. I would quickly comb my hair and go straight onto the stage to speak before hundreds of students.”

Though physically draining, he found satisfaction in knowing he was personally doing justice to the students. “My faculty could not deliver, so I went myself to speak to them.” But the toll was heavy. Nights often stretched until 5 or 6 a.m., and by 10 a.m. he was expected to be fully present before hundreds of young minds. The strain left marks on his health, but he carried on.

Looking back on those years, he described them as a wilderness in his life. “When history is written, this will be remembered. Those I tried to liberate, they were the very ones who hurt me. Because they felt I was not freeing them, but harming them. I told them, 'Go, fly!' They replied, 'We have no wings. You are throwing us out to die. You are our enemy.'”

Each camp bore his signature precision.

Before each camp, Acharya Prashant himself visited every site, finalised the stay, checked food, cleanliness, and even the villagers who were nearby. He would walk the entire area and decide where each discussion would happen.

Participants began their mornings not with chants but with lists—vehicles, routes, who would sit with whom, what question would be discussed on the way. The same order extended inward: every seeker kept a daily diary, noting where attention had strayed, where the mind had slipped into old habits. Efficiency of the outer world was made one with the vigilance of the inner.

Students were given Upanishadic or Kabir verses and told to create songs, plays, or dances expressing their meaning. Once, a first-year student who had never sung before composed and performed a bhajan overnight.

He also introduced an unusual method of study—parallel reading of scriptures. The same group that gathered under the pines at dawn would spend the afternoons aligning verses from Ashtavakra Gita, Avadhoot Gita, and Kabir’s Saheb’s Sakhis. “Find where Kabir meets Ashtavakra,” he would say. The exercise revealed not the differences of language but the oneness of truth beneath names and centuries.

Nandu the Rabbit and the Birth of Veganism

Acharya Prashant once had a pet rabbit named Nandu, a female with an incurable leg injury.

Refusing to put her down, he cared for her daily, tending to her needs with affection and patience. Despite his efforts, Nandu eventually died due to a dietary mistake on his part - a loss that left him devastated.

Just a few days later, while still grieving, he went to watch the film The Ship of Theseus. A scene showed rabbits being experimented upon, and one of them looked uncannily like Nandu. Sitting in the cinema hall, overcome with emotion, he made a life-changing decision: to renounce all animal products completely.

From that day onward, he embraced veganism - not as a struggle, but as a natural extension of his compassion. As he later shared, it has been “quite effortless” to remain vegan ever since.

Jeetu the Courageous Chicken

One evening near Indirapuram, a chicken escaped a butcher's grip and ran in front of Acharya Prashant's car.

He slammed the brakes, saving it. Though the butcher retrieved the bird, Acharya Prashant turned back, sought out the same chicken, and insisted on taking it with him.

It was his first time touching a chicken - restless, pecking, and full of fight. He brought it to Bodhstal, where it lived freely for nearly two years, chasing visitors and earning the name Jeetu (G2).

For Acharya Prashant, Jeetu became a living lesson: courage is to resist bondage, even at great risk. “God helps the courageous chicken,” he said, “but only when it flaps its wings and dares to run.”

The Teaching of Champa the Cat

While in Mumbai to receive the Most Influential Vegan award from PETA, Acharya Prashant's schedule was packed with interviews, shoots, and college talks.

Yet, outside a vegan café, when invited into a small pet-grooming shop, he graciously agreed.

Inside, the dogs and cats warmed up to him instantly. Then came Champa - an elderly cat known to hiss at strangers. To everyone’s surprise, she allowed Acharya Prashant to gently lift her, curling into his arms like an infant and purring softly. The groomer and owner were stunned; Champa had never let anyone else hold her.

The person accompanying Acharya Prashant was anxious about the delay, but he remained calm, radiating warmth and stillness. In that moment, he embodied Lao Tzu’s words: “Nature does not hurry, yet everything is accomplished.”

That same day, he went on to deliver a five-hour college talk, and by night was at a Hindi movie - before another full day of sessions and travel back to Delhi.

When the Movement Became a Foundation (2015-2019)

We have committed ourselves to the highest ideal that humanity can envisage.

Acharya Prashant founded the PrashantAdvait Foundation (PAF), a non-profit organization dedicated to bringing a scientific attitude and lived wisdom into daily life.

The earliest recordings had begun in 2011, with only one English YouTube channel at first. A Hindi channel was added in 2014. By 2017, thousands of talks were already recorded, quietly forming the foundation of his digital presence. These were years of quiet, consistent effort - sowing seeds without expecting quick recognition.

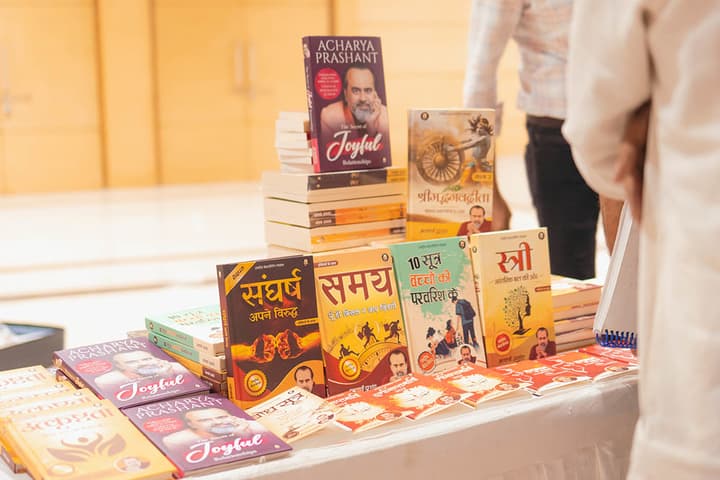

Around the time the Foundation was formally registered in 2015, books also began to be published. Volunteers transcribed Acharya Prashant’s talks into manuscripts, compiled them into volumes, and carried them for printing. These were raw books, filled with typos, stitched together with sincerity rather than polish - but they carried a force that could not be ignored.

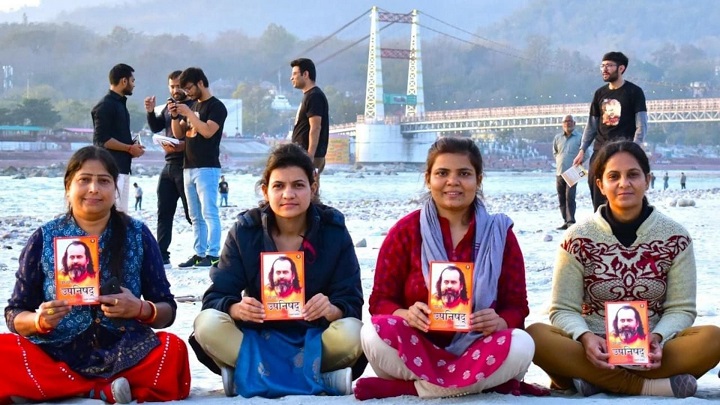

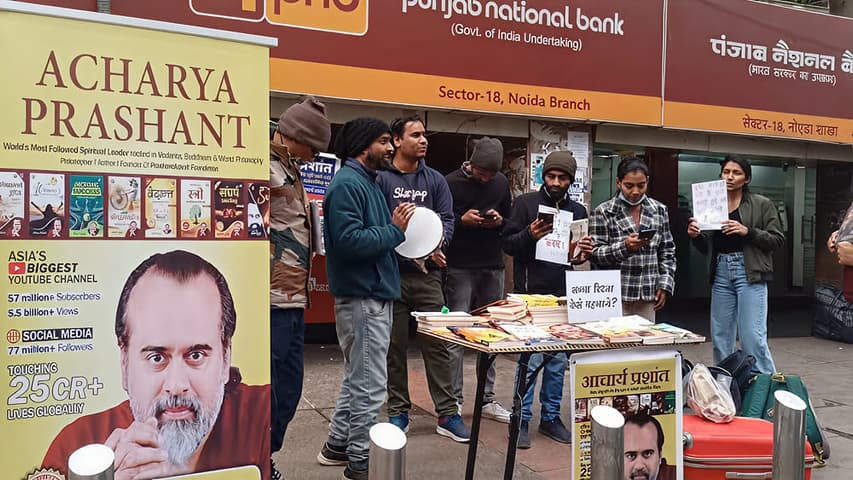

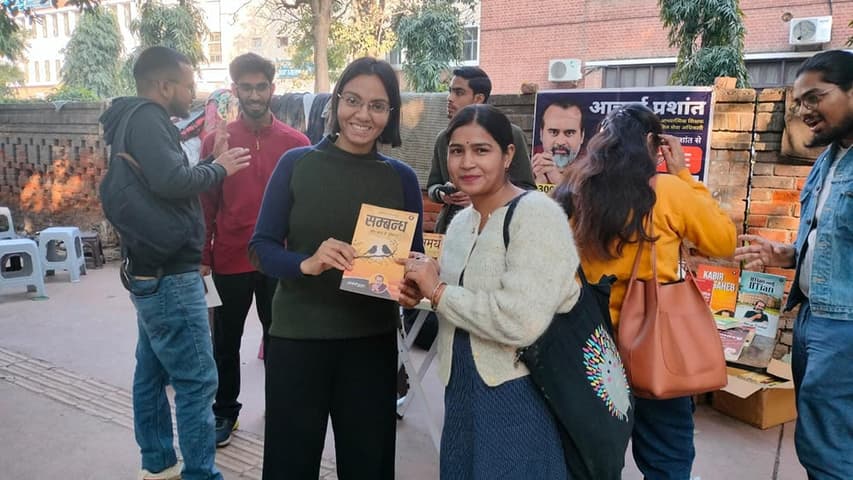

Acharya Prashant had thrown a challenge to the youth: “If you have truly understood something, then don't keep it to yourself. Go out on the streets and talk to people. See if you can explain it to others. If love has really happened to you, then sing your love-song openly.”

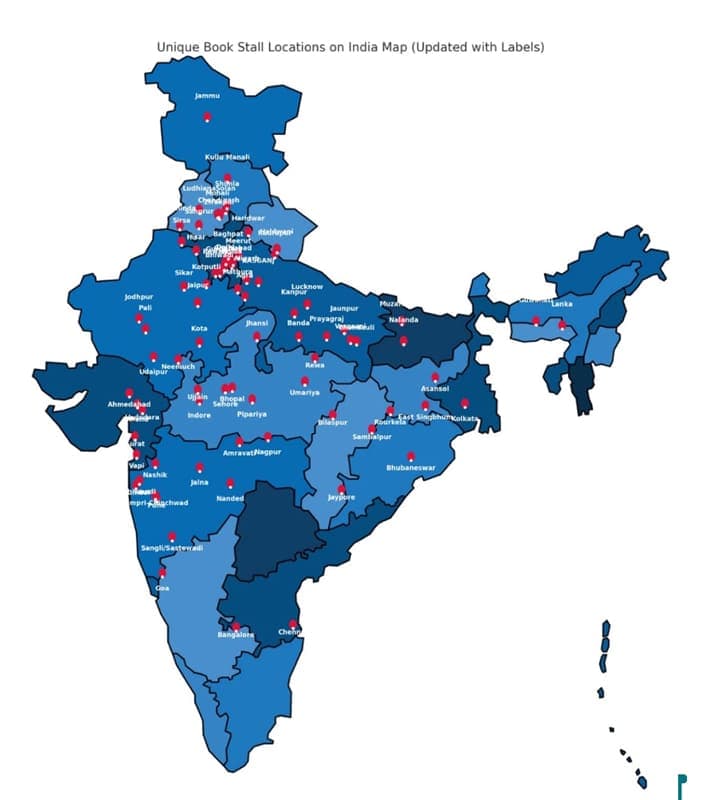

Books needed readers, and so bookstalls appeared. In fact, even before the registration was formally complete, between October and December of 2015, the first stalls had already been set up with the newly printed titles.

At the stalls, conversations were not hurried. A single passerby might be held in dialogue for half an hour - persuaded, reasoned with, even gently provoked. “It was never about selling,” Acharya Prashant later said. “It was about what you became in the process.”

They stood until midnight, sometimes returning home only when the police dispersed them. During demonetization, when ATM queues stretched into the night, they approached people waiting for cash: “You are standing here anyway, why not read something worthwhile?” Most refused, some mocked, but a few listened - and the youth persisted.

Acharya Prashant himself would sometimes cycle or drive to the stalls, quietly carrying food. Volunteers rarely ate; from five in the evening till late at night they would not leave their posts. He would hand them samosas or dinner packets, smiling as he watched them argue passionately with strangers.

There were lighter moments too. The books carried his photograph on the cover, and people would glance from the picture to the man standing before them, food in hand. “Isn't that you?” they would ask. Acharya Prashant would laugh and deny it: “No, no, that's not me. Forget me, read the book.” Sometimes he even handed out a copy himself while insisting that it was someone else on the cover.

The spirit at the stalls was never commercial. No book was given for less than ₹300, and most were priced at ₹400 or more. “How can something priceless be sold cheap?” the volunteers insisted. It was not business but idealism - a refusal to compromise on the worth of truth.

The hardships were real: long hours in heat and rain, indifference from passersby, ridicule from friends or relatives. Yet those very hardships forged resilience. Many who would later carry great responsibilities in the Foundation first learned to stand tall at these bookstalls - speaking for truth, enduring rejection, and discovering strength.

“Do not think it is a small thing you are doing,” Acharya Prashant reminded them. “When you decide to stand with truth, you have already won. The outcome after that is secondary.”

Meet The Master

Amid the growing scale of his work, Acharya Prashant, in 2017, also created an intimate space for seekers who wished to engage with him more directly - Meet the Master. These were not public discourses or large gatherings, but close, personal conversations, where seekers from across the globe could sit before him and speak from their hearts.

The sessions were open to all, ensuring that anyone, regardless of background or means, could come and sit before him in search of clarity. People came with questions about relationships, fear, work, purpose, or simply the meaning of life - and often left in silence, their questions dissolved rather than answered.

Through Meet the Master, Acharya Prashant returned to the oldest form of philosophical dialogue - the direct meeting between teacher and seeker. It became a refuge for those who sought not miracles, but understanding; not blessings, but clarity.

The Myth Demolition Tour

Around the same time in 2016, Acharya Prashant also launched what came to be known as The Myth Demolition Tour - a series of wisdom gatherings across cities like Rishikesh, Dharamshala and Greater Noida. These sessions were not designed to soothe but to shake. Their purpose was to expose and dismantle the deeply ingrained falsehoods that bind the human mind - the myths of ego, identity, religion, free will, and worldly success.

“The false must be seen as false,” he would say. “Only then can Truth reveal itself.”

Seekers came expecting answers but left with questions - real ones, the kind that demanded courage instead of comfort. Each session was an encounter, a demolition of illusion. What remained was not confusion but clarity - a cleaner space within, where truth could begin to breathe.

A treasure with no audience: By 2018, nearly 3,000 videos had been uploaded to YouTube, but the channel had only 2,000 subscribers. Acharya Prashant later described that time as one of helplessness.

“Those 3,000 videos were the essence of my life, my very blood. They were a treasure I longed to share with the world. Yet, after seven years of consistently speaking, I had only accumulated 2,000 subscribers. Many of those videos contained things I could probably never create again - words spoken then that perhaps I may not be able to utter now. The despair deepened - what were we doing wrong?”

In 2019, a bold decision was taken: to go “all out.”

“A decision was made: come what may - danger, the loss of our home, or death itself - we would go all out, holding nothing back.”

This marked the beginning of a new phase—strategic outreach, dedicated teams, and uncompromising commitment to spreading the message. From this point, the Foundation’s every effort and resource was directed toward ensuring that timeless wisdom could reach people in a language and medium they could relate to. Investments were made in better video production, outreach, and the infrastructure needed to sustain the growing work.

The financial strain was immense. When the Foundation lacked resources, Acharya Prashant sold his own house in Noida to keep the work alive. The current headquarters, Bodhsthal, is his father’s property that was donated to the mission. Over time, every rupee of his personal savings was poured into the Foundation. Alongside these financial sacrifices came his physical struggle—relentless schedules, constant speaking, and unyielding travel.

Kabir Saheb

In one of his talks in 2019, he described himself as a “fanboy” of Kabir Saheb, calling him his “superhero.”

What inspired him was Kabir Saheb’s ability to stand utterly alone, defying orthodoxy in the very heart of Varanasi. Proclaiming himself “कबीर कुत्ता राम का” (Kabir, the dog of Ram), Saint Kabir displayed his utter surrender to the Truth. He dismissed empty rituals with piercing clarity: “पाथर पूजे हरि मिले, तो मैं पूजू पहाड़”—if God could be found in stones, then mountains were holier still.

Kabir’s Saheb’s simplicity also struck him. On Maya, He said: “जो मन से न उतरे, माया कहिए सोय”—that which clings to the mind is Maya. On time and death: “जेति मन की कल्पना काल कहावे सोय.” For Acharya Prashant, this was the rare union of brutal honesty and childlike simplicity.

He often highlighted Kabir Saheb’s unsparing words against cruelty to animals: “अश्वमेध, अजमेध, सर्पमेध, नरमेध, कहे कबीर अधर्म को धर्म बतावे वेद.” For him, Kabir Saheb was the vegan of his times, fearlessly confronting even the scriptures when they justified violence.

“If I am very unwell and dying, don’t bring me Gangajal (holy water),” Acharya Prashant once said. “Just sing Kabir Saheb. Not that it would take me to heaven—it might actually make me get up.”

An incident from his own life shows how deeply Kabir Saheb’s presence lives within him.

Late one night near Almora, riding his motorcycle at high speed in heavy rain, he found himself humming a Kabir bhajan. For nearly two hours, the song flowed on as he rode. At one point, the bike slipped on the wet road, leaving him injured with a sprained ankle. Yet even through the danger and pain, the humming never stopped.

“I didn’t even notice it,” he recalled. “As if there were two of me—one who is indulged in his worldly duties and the other who is doing his work. And this 'other' has no interest in the world.” He connected this to the Upanishadic image of two birds on a single branch—one eating, the other simply watching. For him, this was the art of living: letting prakriti carry out its duties, while the purush remains untouched in silence.

The same day, despite the injury, he delivered a long session. Midway, someone pointed out that blood was still flowing from his wounds.

The Storm is Raging Way Out of the Teacup (2020-Present)

The storm of clarity outgrew its walls, reaching every corner of the world.

The year 2020 brought an unexpected blow.

With the outbreak of COVID-19, the Foundation’s primary source of revenue - wisdom camps - came to a complete halt. Camps had been the heartbeat of both learning and donations, but overnight, they stopped. Members returned to their homes, and the organization faced one of its toughest phases.

Yet, from this pause came a realization: if physical gatherings could be disrupted so easily, the future had to be digital. The Foundation began experimenting with new models - including offering e-books for as little as ₹1 - and reimagining its structure around online platforms.

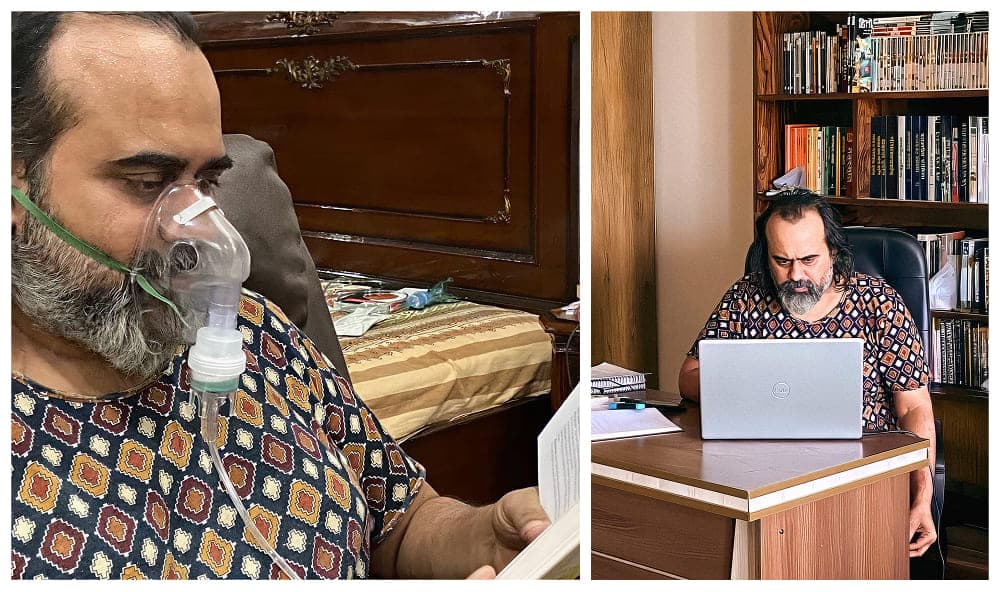

During this period, Acharya Prashant himself was struck severely by COVID-19, running the risk of black fungus infection.

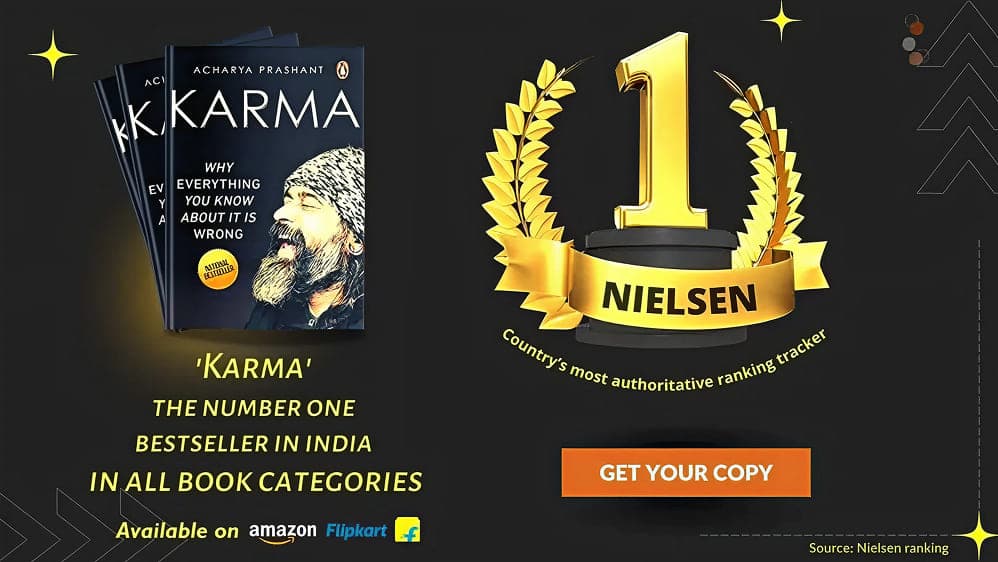

Even in illness, he refused to pause his work. He continued writing, completing his book Karma, which was later published by Penguin and went on to become an Amazon Bestseller as well as a Nielsen bestseller.

By June 2021, as the pandemic eased, wisdom camps resumed.

In December that year, one of the largest gatherings, the Vedant Mahotsav, was organized. But a deeper transformation was already underway.

The Ghar Ghar Upanishad campaign was launched on Vedant Diwas, 1 October 2021, with the resolve to deliver the Upanishads and their meanings to 20 crore households.

By the end of 2021, the Acharya Prashant Android App was launched, followed soon after by the iOS version in early 2022. With the app in place, a new possibility opened up: online wisdom sessions.

In May 2022, Acharya Prashant began systematic discourses on the Bhagavad Gita.

By the end of the year, three chapters had been completed. The demand grew so strong that seekers requested he start again from the very first chapter. Responding to this, Gita Samagam was launched — an online platform where seekers could study the Bhagavad Gita and the Ashtavakra Gita.

It was also around this time that he suffered a serious accident in Rishikesh, where a head injury led to temporary memory loss.

For a few hours, he could not recall names, events, or even how he had reached his place. Realizing that memory was slipping, he quickly sat down and dictated instructions for how the Foundation should continue in case he was gone - covering books, publishing, and the support of those working with him. By the next day, his memory returned, but the incident left a deep impression. It became, as he later put it, a “lesson in impermanence,” sharpening his urgency to work faster and harder, knowing how suddenly life could be interrupted.

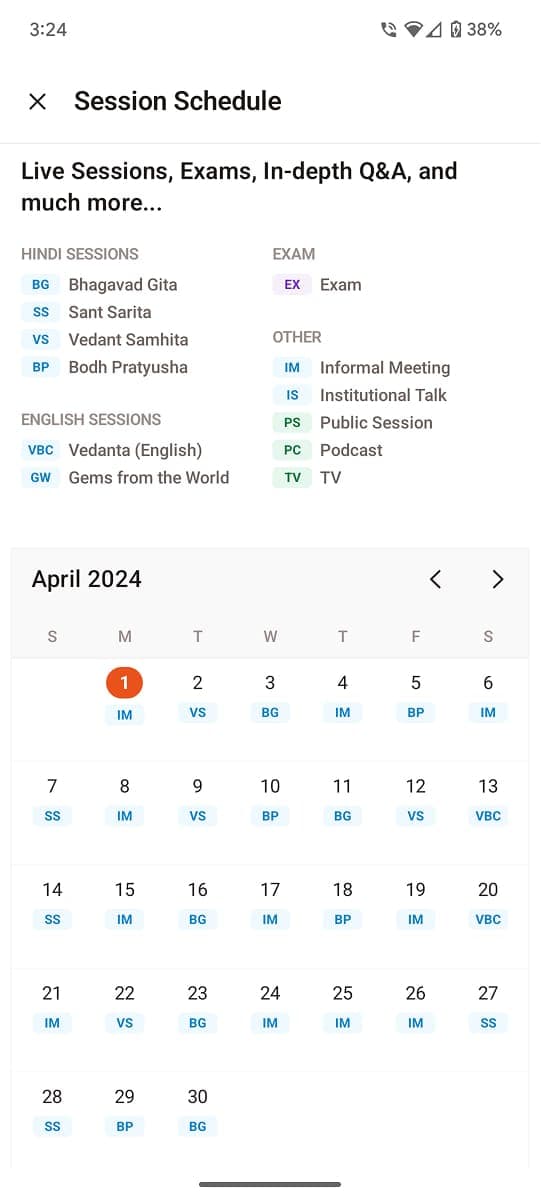

In the year 2023, Acharya Prashant, who had earlier conducted only five sessions a month, increased the frequency and expanded the scope. New series were introduced: Vedant English, Sant Sarita, Kathopanishad, Tao Te Ching, and Shunyata Saptati. Each session would last around four hours, and at times stretched to six or even seven, as questions kept flowing and the dialogue deepened. Through this, seekers were drawn closer to timeless wisdom on contemporary platforms. This digital leap transformed everything.

Five million milestone on YouTube

Meanwhile, the YouTube channels were witnessing rapid growth. What had once been just 2,000 subscribers in 2018 had soared to over 5 million by 2023. Acharya Prashant’s videos began reaching millions worldwide, and the Foundation’s community expanded from a small circle of dedicated followers into a truly global audience.

But something very important was missing. In a 2023 speech, Acharya Prashant spoke candidly about the struggles he and the Foundation were facing.

“I am still in the thick of battle and conflict. My talks are the stories that I have actually experienced.”

When asked what he missed from his corporate life, his reply was blunt: “Competence, competence.” He lamented the irony that the world of “pleasure and greed and consumption” is overflowing with talent and drive, while the field that stands for courage, honesty, and freedom is barren in comparison. “I don’t find competence here. I don’t even find that level of enthusiasm and drive here,” he said.

He noted that those who do join his mission often lack the eagerness and energy found in corporate spaces. “In my camp, we see laziness, indifference, demotivation,” he remarked. The reason, he explained, was simple: “My battle offers no gratification, no promises of money, sex, or prestige. It only offers dissolution - a place where you can finally rest in peace.”

This made attracting and retaining talent extraordinarily difficult. He shared that many of his seniors and juniors from IIT and IIM had been deeply drawn to his work for years, yet “their paymasters keep bidding very high, and all of them are available to be auctioned.”

The resistance was not only financial but also social. He spoke of spouses who dragged their partners away from the Foundation, questioning, “Why did you marry me if this is the work you want to do?”

Despite all this, he reaffirmed his commitment: “We have committed ourselves to the highest ideal that humanity can envisage, and yet people are afraid and indifferent, not merely reluctant but actually in opposition. Right now I struggle for both funds and talent — that’s a pain point. But still, the going is great and I would not trade it for anything under the sun.”

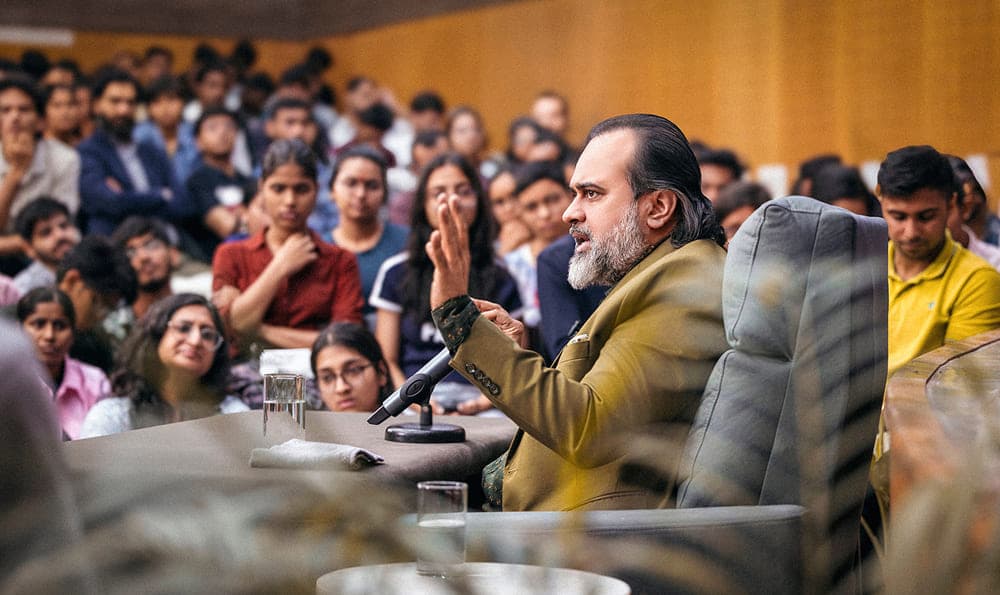

By 2024, the Gita Community around Acharya Prashant had grown into a living movement. His teaching program engaged more than 30,000 students worldwide.

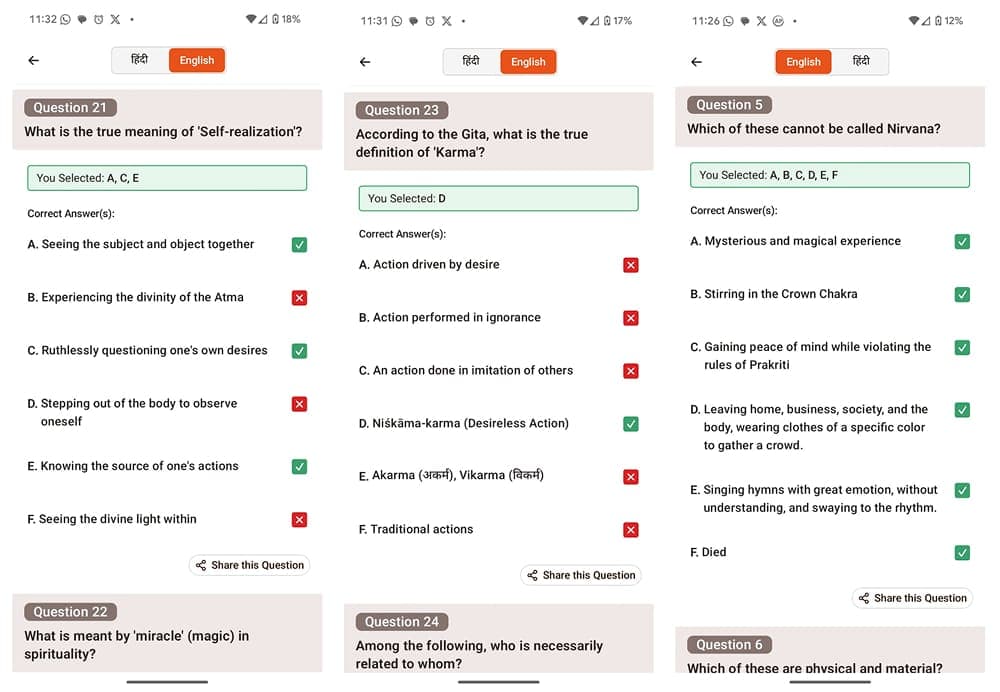

Each session carried a distinctive rhythm: beginning with a deep exposition of shlokas from the Gītā, Vedānta, Buddhism, world philosophy, or the songs of saints, and then opening into dialogue where seekers brought their most personal questions. Examinations and written reflections became central to the process, allowing students to test their understanding and articulate how the teachings were transforming their lives.

In April 2024, he introduced informal meetings with the community

Sessions devoted entirely to personal questions of seekers from all over the globe. He described these conversations as moments of genuine intimacy, often saying that the community felt like his own family.

Meanwhile, the pace of teaching intensified. What had once been five sessions a month grew to thirteen, then twenty-one, and eventually to daily discourses. Acharya Prashant often reminded his students that it is precisely when they are away from him that they are most vulnerable to Maya; therefore, he refused to let even a single day pass without a session.

This intensity came at a cost. A severe throat condition, long neglected, now demanded attention.

After spending an entire day in the hospital, he entered a session and spoke candidly of what the doctors had told him: his throat had become “scratched and completely like wood - dry, inflexible, worn down.”

A deep blood vessel had ruptured, and the treatment required him to sip warm liquids every five minutes, avoid solids, and even restrain himself from laughing. “I didn’t take care,” he admitted, “and the matter escalated.”

Yet he insisted that such an obstruction did not mean the work could stop.

Instead, he would adapt. Drawing an analogy, he explained: “When there is a shortage of money at home, you don’t cut your child’s school fees or your parents’ medicine. You cut from elsewhere. Similarly, if the throat cannot be spent much, the session times will not be cut. Instead, wherever else the throat is used, that will be stopped. You wouldn’t stop your child’s schooling, would you? Just as you cannot stop that, why should I stop your sessions?”

For him, the sessions were non-negotiable.

Speaking was like paying for a child’s education - it simply had to continue. The adjustments came elsewhere: fewer casual words, greater efficiency in expression, condensing where ten minutes of speech could be delivered in five. “This too,” he said, “is an opportunity - to streamline, to become more efficient.”

Even in pain - sometimes with blood in the sink or on the bed after waking - he continued speaking daily. For him, the discomfort of the body was never reason enough to withhold the words of Vedanta from those who needed them.

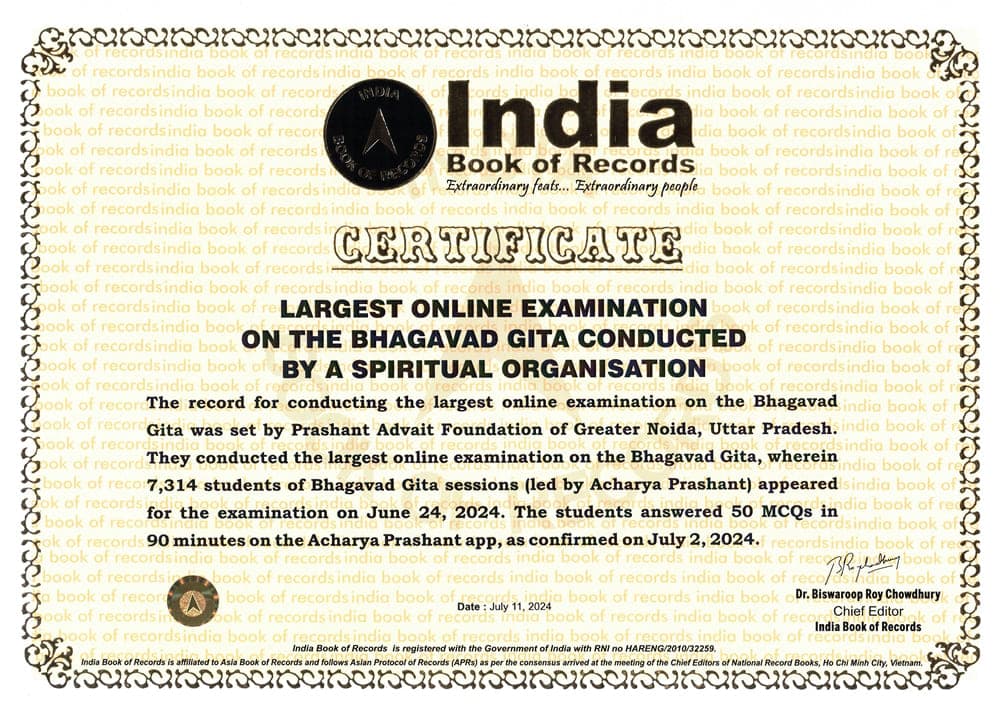

In June 2024, another milestone came when the Foundation conducted the world's largest Gita Exam, with 7,314 students participating—a feat recognized by the India Book of Records.

Acharya Prashant personally designed the evaluation, insisting that it embody the Vedantic principle of Neti Neti (not this, not this).

More than rewarding correct answers, the focus was on penalizing wrong ones, so that seekers would learn which paths must be abandoned. “A wrong answer is a wrong path,” he explained, “and Vedanta’s first work is to close the wrong path. So heavier penalties must go to those who choose wrongly.”

He also stressed that Adhyatma (spirituality) is not dull ras - a natural joy. That spirit was present even in the exam, where elements of wit and irreverence exposed hollow traditions and false religiosity, reminding seekers that true spirituality is vibrant, alive, and full of joy.

Just a week later, on 1 July 2024, his YouTube network crossed 50 million subscribers.

In only six years, what had begun with a few thousand followers had grown into the world’s largest wisdom platform.

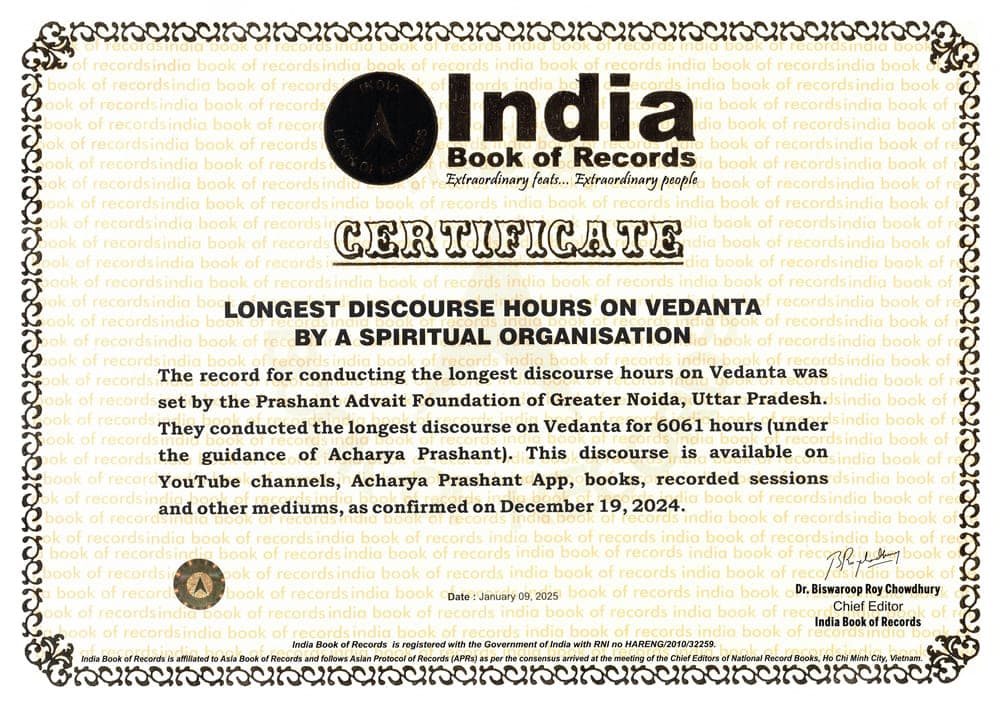

In February 2025, the Foundation was recognized by the India Book of Records for conducting the longest continuous discourse on Vedanta - a staggering 6,061 hours of sustained teaching.

What began with just a handful of sessions had now become a marathon exploration of timeless wisdom.

By July 2025, the community had grown to more than 100,000 students worldwide - seekers drawn from every corner of the globe. What had once been small gatherings was now a vast classroom without borders, united by a shared love for a liberated life.

Within this expanding fellowship, transformation runs deep. Members report a profound shift in their relationship with religion and self: rituals give way to understanding, faith to enquiry, and belief to clarity.

Many have changed their diets, simplified their lives, and withdrawn from consumerist habits. Women are stepping into workplaces and claiming autonomy once denied; young people are discovering strength in discipline and purpose; caste and national identities are loosening their hold.

Compassion for animals and awareness of the planet have become part of everyday ethics. What unites them is not ideology, but the courage to live truthfully, even at the cost of social comfort.

As the global audience grew, there was increasing demand for English sessions.

In response, Acharya Prashant introduced Gems from the World — a treasury of timeless stories and teachings from Zen, Sufi, Jewish, and Existential philosophies.

These sessions showed how the same truth has echoed across cultures and eras, helping seekers worldwide connect more deeply with the teachings.

In August 2024, the community independently began setting up bookstalls across towns and cities in India.

What started as a few scattered stalls soon became a powerful movement. Within a year, the stalls were covering most parts of the country.

These bookstalls were not just points of sale; they became places of connection and awakening.

They carried Acharya Prashant’s words into marketplaces, streets, and neighborhoods, turning ordinary spaces into sites of quiet transformation. What had begun as an individual initiative grew into a collective force - a mass awakening across the world.

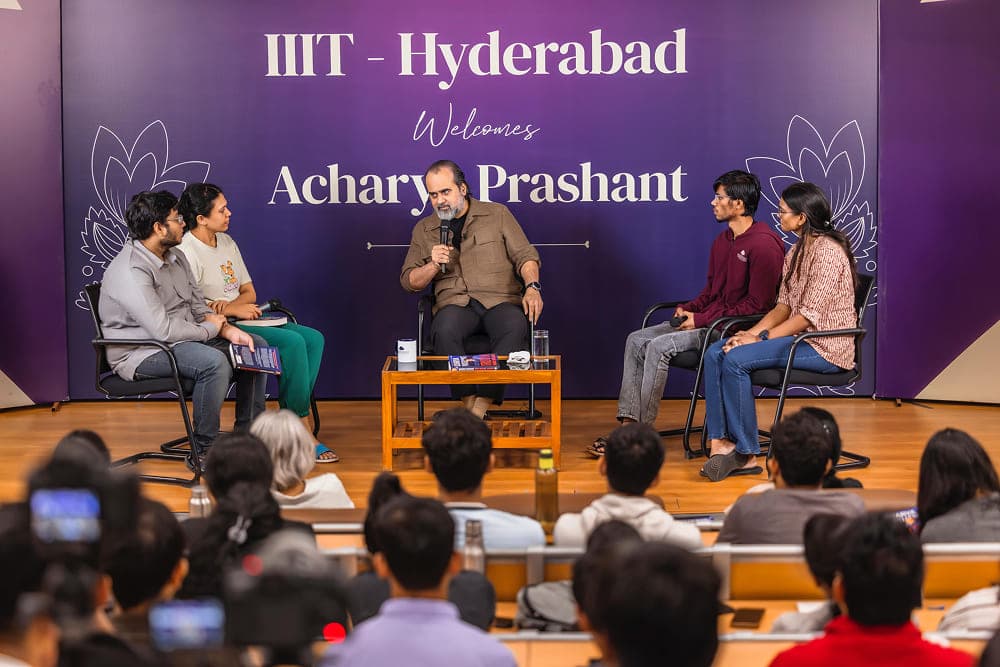

Dialogues with Academia

Among all segments of society, the youth have responded to him most naturally.

For over two decades, Acharya Prashant has been in continuous dialogue with students—ranging from small-town colleges to institutions like the IITs, IIMs, IISc, and UC Berkeley. In spirit and method, he resembles Socrates—uncompromising in inquiry, disarming in simplicity, fearless before convention.

Introducing him at BITS Goa, student Mubariz Khan said:

“I have been listening to Acharya Ji for the past three years, and I first met him the way most great students meet great teachers in today’s world—through YouTube. My brother used to play his talks, and one day I overheard a few minutes of a discourse. Within moments I was thinking, who is this person dismantling my ideas faster than I can defend them?”

Some nights it was an hour; other nights six, seven or even eight. I was deeply suspicious of abstract philosophy, but his words were different—they weren’t the same soft reheated platitudes you often hear. He didn’t politely suggest that I reconsider my beliefs; he walked in, knocked everything down, and left me wondering why I had such bad furniture in my mental house for so long.

What struck me was that he wasn’t dismissing science or facts in the name of spirituality—something far too common today. He could speak of the essence of the ancient masters without losing touch with reason and the world we live in. It was grounded, deeply human, and accessible even to a rebellious teenager like me.”

Acharya Prashant engages not only with students but also with faculty and thinkers. In a notable dialogue at IIM Bangalore with Professor Trilochan Sastry—his former professor at IIM Ahmedabad, founder of the Association for Democratic Reforms, and former Dean of IIM Bangalore—Prof. Sastry remarked:

“The essence of Hinduism was revived by Krishna, by Buddha, and Shankara—and maybe people like him [Acharya Prashant] will revive it again.”

Across college campuses, he awakens clarity and a deep urge to inquire in young minds.

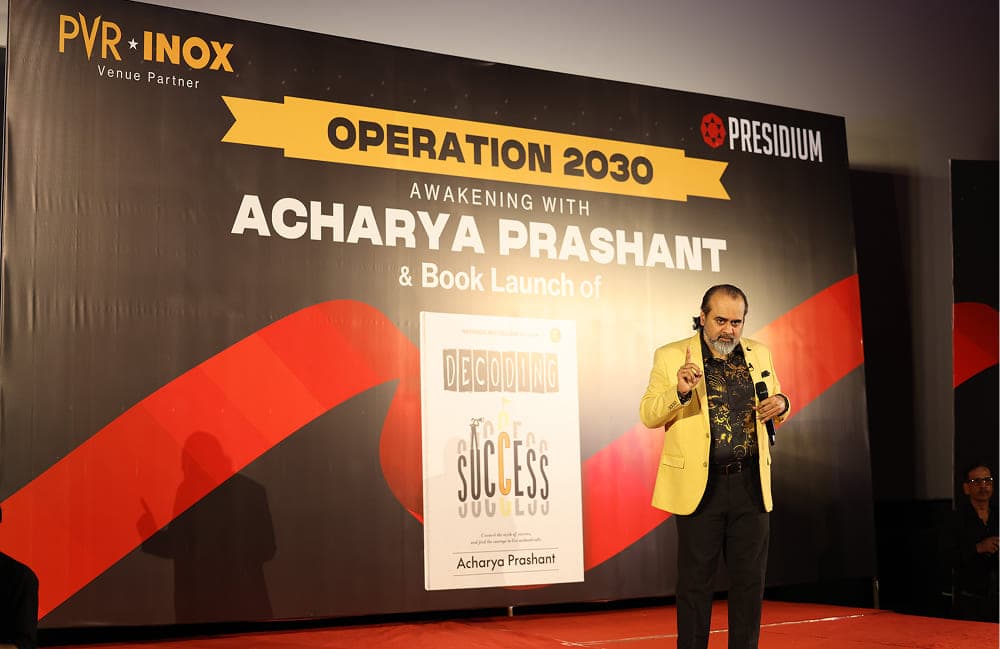

Operation 2030

It is an emergency call to raise awareness about the climate crisis

After nearly a decade of addressing the climate crisis, Acharya Prashant formally launched Operation 2030 in 2025 as a dedicated mission to act on the UN’s climate deadline.

Its seeds had not been sown in policy rooms but in his heart. “Climate change is nothing but a consequence of how we are on the inside. Let’s treat the inside,” he often said.

For more than a decade before climate change became a household phrase, he was speaking of humanity’s forgotten relationship with nature.

Operation 2030 was his response to the United Nations’ call to limit global warming to 1.5°C by 2030 - a deadline beyond which scientists warn the planet faces irreversible damage.

Unlike conventional climate campaigns, Acharya Prashant emphasized that the outer climate mirrors the inner one: when the human mind is restless and greedy, the Earth itself bears the cost. Real change, he argued, begins within - at the level of one’s food, family, and consumption.

“In every being, the same life breathes.”

For him, care for animals and the planet was not an abstract principle but an intimate reality.

“Come close to a stranger, an insect, an animal, a bird… and it will become very difficult for you to say that the animal is not a person.” Under his guidance, more than a lakh families embraced vegetarianism or veganism - not merely as a dietary choice but as a transformation of consciousness.

“Do not turn vegan out of pity,” he insisted. “Turn vegan in your own self-interest - because in killing the other, you are killing yourself.”

Operation 2030 has since grown into a global movement, with Acharya Prashant recognized internationally for linking philosophical clarity with ecological responsibility. He has been honored as Most Influential Vegan by PETA and as Most Impactful Environmentalist on World Environment Day - acknowledgments of his role in inspiring people to rethink their relationship with nature.

Bleeding Throat, Unyielding Spirit: Acharya Prashant’s Fight for the Voiceless

On the evening of November 15, just hours before a scheduled Gita session, a message arrived from Gauri Maulekhi, a prominent animal rights activist.

She requested Acharya Prashant to join her in Patna the following morning to meet the Chief Secretary of Bihar and address the press about the Gadhimai festival in Nepal. This was no ordinary request. It was a plea to save thousands of animals and to raise a voice against a centuries-old practice of cruelty disguised as tradition.

“Would Acharya Prashant be able to catch the 8 AM flight on the 16th?” she asked.

At first, the idea seemed impossible. The Gita session that evening was expected to continue until 2 AM. For an 8 AM flight, he would need to leave by 4 AM, leaving no time to rest.

Moreover, the following day included a scheduled Gita students’ exam, and the Foundation was also preparing for the world’s largest open Gita exam on the 17th, followed by another late-night Gita session. It seemed unrealistic to fit in this additional journey and effort.

When the matter was brought to him, he agreed without hesitation.

“Shall we reschedule the sessions or exams?” someone asked.

Continuing his work, Acharya Prashant calmly replied, “Why?”

His foundation members couldn’t hold back their surprise. “In this weather, with your health, you’re planning to conduct a Gita session, prepare and oversee exams, travel from Greater Noida to Delhi, then to Patna, meet the Chief Secretary, address the press, and return to conduct yet another session and exam - all within two days?”

“Doctors have advised you to take a 10-day rest to heal your throat, and yet you are scheduling at least 8 hours of speaking over the next two days?” someone added.

For the past five months, he had endured severe throat pain, often waking to find his pillow stained with blood or spitting blood after prolonged speaking sessions.

Despite this, he answered simply, “It’s not just about me—thousands of animals’ lives can be saved. I have to go.”

That night, he conducted the Gita session as planned, which stretched until 2 AM. While most attendees retired to rest, he continued working—preparing questions for the exam and listening to student reflections. By 4 AM, without a moment of rest, he left for the airport. Exhaustion was evident on his face, yet he greeted security personnel and fellow passengers with warmth.

On arriving in Patna, his first meeting was with the Chief Secretary of Bihar. They discussed the alarming scale of animal sacrifices at the Gadhimai festival and the illegal trafficking of animals across the India-Nepal border. In 2022 alone, over 200,000 goats had been slaughtered in Bihar’s Banka district during Dussehra.

Acharya Prashant presented a letter addressed to Bihar’s Chief Minister, highlighting these concerns and calling for stricter implementation of anti-trafficking laws. Citing Supreme Court directives, he emphasized the need to align practices with India’s cultural foundation of Ahimsa.

From the meeting, Acharya Prashant proceeded directly to a press conference at the hotel. Despite being awake for over 36 hours, he spoke in detail about the atrocities of the Gadhimai festival.

In 2009, over 500,000 animals were sacrificed at this event. Due to collective efforts, this number has now reduced by 60–70%, but the fight is far from over.

“True religiosity does not demand violence”, he said. “Religiosity and compassion go hand in hand - never religiosity and cruelty.”

Although drained from continuous work and travel, Acharya Prashant found time to meet students from the Gita Mission program who had come to see him. For over 1.5 hours, he spoke with them, laughed with them, and inspired them. His exhaustion was visible, yet his face radiated kindness and energy.

That evening, as he prepared to return to Delhi, his flight was delayed. At the airport, he continued to meet and engage with people who recognized him. During the flight, he discussed with Gauri Maulekhi ways to further help animals and address the systemic issues behind such cruelty.

Back in Delhi, Acharya Prashant resumed work without rest. He began preparing for the world’s largest Gita Open Exam, involving thousands of participants worldwide. This was not just an exam; it was an effort to connect people with the profound truths of the Gita.

By the time the exam concluded, it was already 10 PM, and another Gita session began.

In that session, Acharya Prashant said, “Desires rely on tomorrow, but faith only knows the present. If the present is complete, thoughts of the future vanish.”

His words opened new dimensions for the listeners. Such dedication might seem impractical to an outsider, but those who have seen Acharya Prashant live his teachings know their depth.

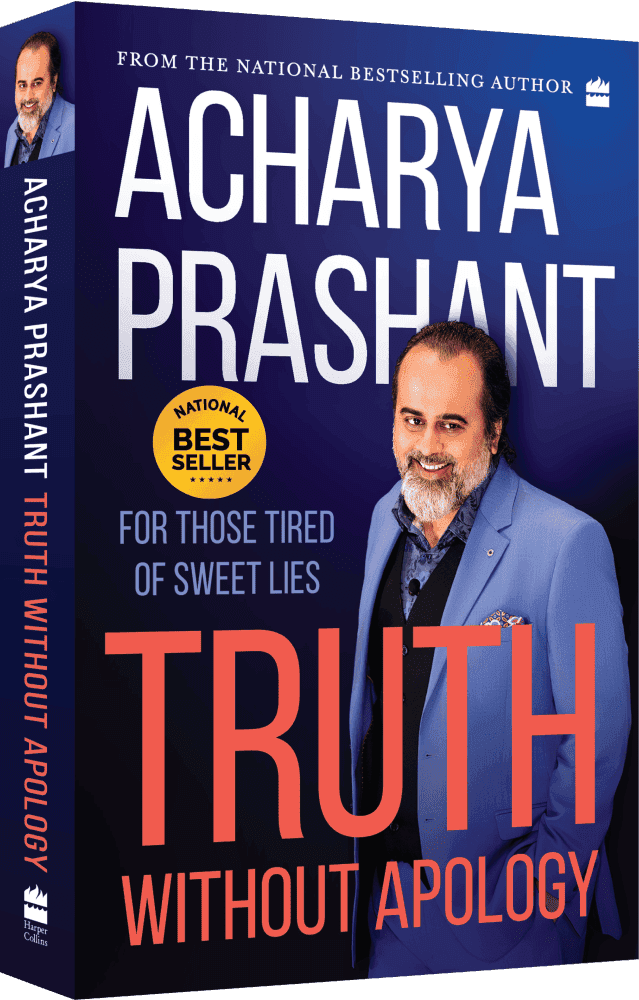

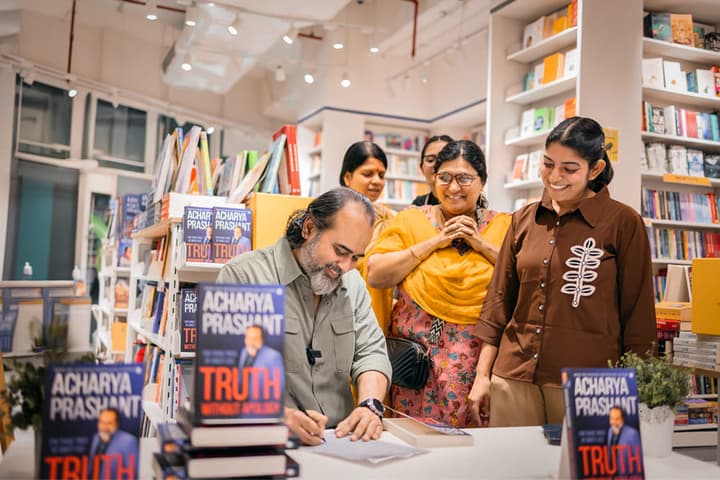

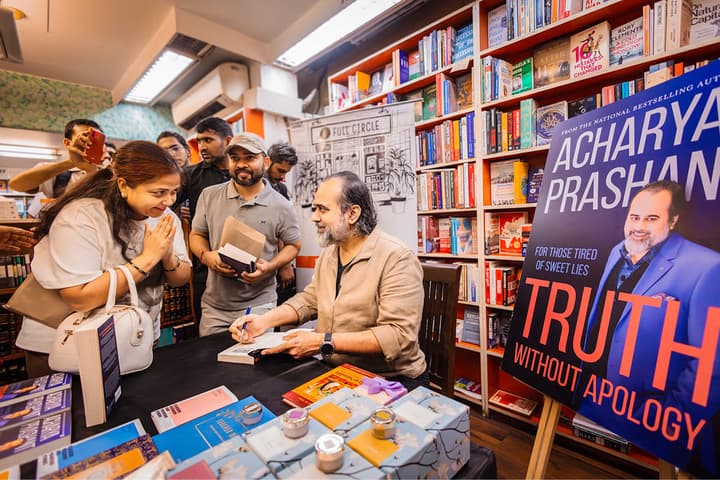

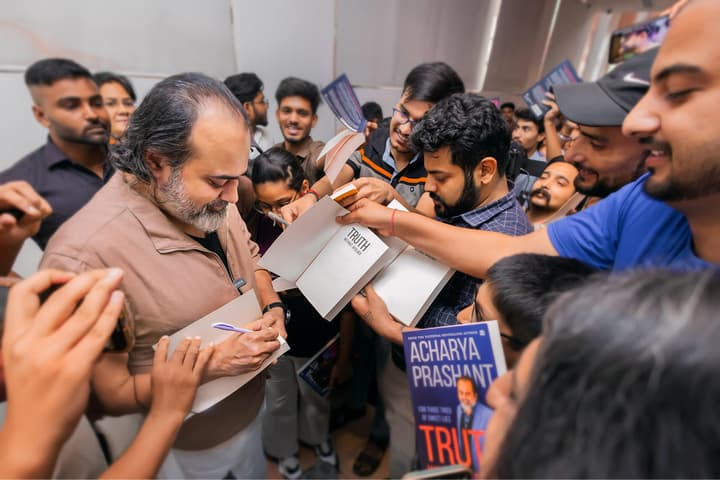

Truth Without Apology

For Those Tired of Sweet Lies

The Story of this Book

Truth Without Apology is not a metaphor here. It's a lived reality.

Some stories aren't told because they are dramatic. They're told because they are necessary. This is one such story: a quiet storm of grit, pain, and unrelenting truth.

When the Body Becomes the Battlefield

Imagine waking up every morning for twenty-six years knowing your own body is not your ally. Inflammation like liquid fire coursing through your veins. Energy seeping away like water through cracked earth. Skin breaking down, betraying you. Your flesh turning against you in ways that textbooks cannot capture.

Now imagine choosing, despite all of this, to show up every single day, for nineteen continuous years. Teaching until your voice cracks. Guiding when your hands shake. Giving when you have nothing left to give. Without a pause. Without an excuse. Without a single day of surrender.

That was Acharya Prashant's life. And just when he had learned to dance with suffering, life raised the stakes one final time.

When Even Endurance Breaks