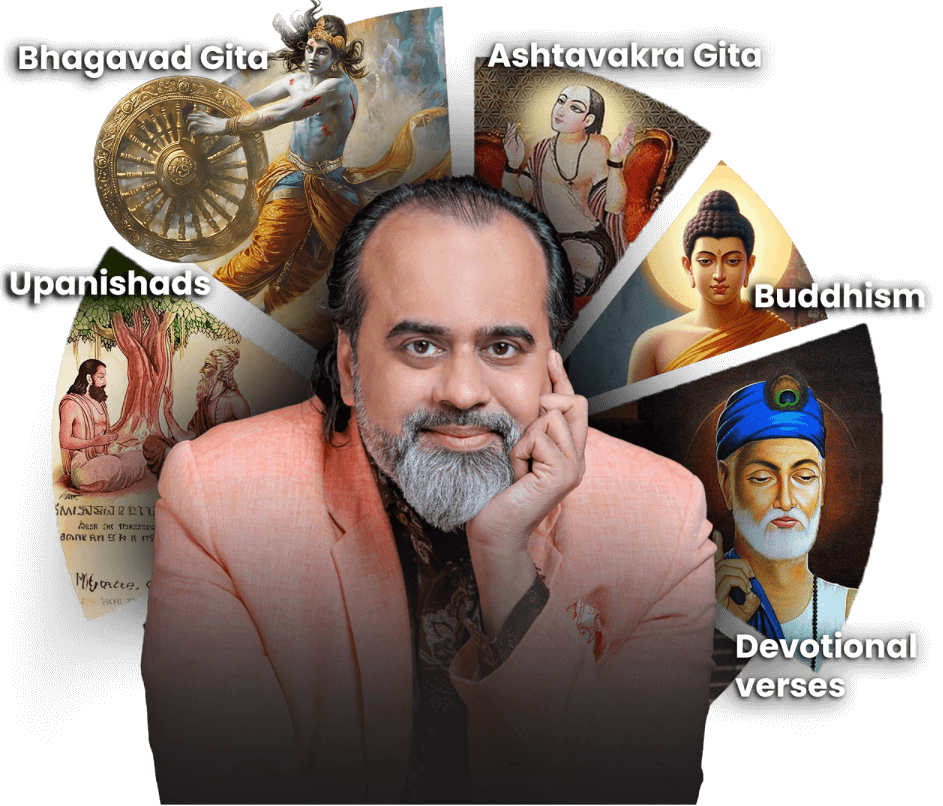

Hear, concentrate, meditate, dissolve || On Advaita Vedanta (2019)

इत्थं वाक्यैस्तथार्थानुसन्धानं श्रवणं भवेत् । युक्त्या संभावितत्वानुसन्धानं मननं तु तत् ॥

itthaṃ vākyaistathārthānusandhānaṃ śravaṇaṃ bhavet yuktyā saṃbhāvitatvānusandhānaṃ mananaṃ tu tat

‘To listen’, thus is to pursue by means of sentences their import. On the other hand, ‘thinking’ consists in perceiving its consistency with reason.

~ Adhyatma Upanishad, Verse 33

✥ ✥ ✥

ताभ्यं निर्विचिकित्सेऽर्थे चेतसः स्थापितस्य यत् । एकतानत्वमेतद्धि निदिध्यासनमुच्यते ॥

tābhyaṃ nirvicikitse'rthe cetasaḥ sthāpitasya yat ekatānatvametaddhi nididhyāsanamucyate

‘Meditation’ is indeed the exclusive attention of the mind fixed on (the import) rendered indubitable through listening and thinking.

~ Adhyatma Upanishad, Verse 34

✥ ✥ ✥

ध्यातृध्याने परित्यज्य क्रमाद्ध्येयैकगोचरम् । निवातदीपवच्चित्तं समाधिरभिधीयते ॥

dhyātṛdhyāne parityajya kramāddhyeyaikagocaram nivātadipavaccittaṃ samādhirabhidhiyate

‘Concentration’ is said to be the mind which, outgrowing the dualism between the meditator and meditation, gradually dwells exclusively on the object (of meditation) and is like a flame in a windless spot.

~ Adhyatma Upanishad, Verse 35

✥ ✥ ✥

Questioner: What do these verses imply? Explain everything.

Acharya Prashant: First of all, the translation is not quite accurate. That which is being talked of as concentration here is not really concentration.

If the topic of the course is Advait Vedanta… I don’t know how the readings have been decided and which particular books are being referred to; in fact, why only Adhyatma Upanishad . I don’t know how the readings have been selected. If the topic is Advait Vedanta, go to the principal Upanishads—Katha, Kena, Isha, Chandogya, Brihadaranyaka. I am not sure why these particular readings are being dealt with.

In the verses from the Upanishad that you have quoted, these four things have been talked of: listening, thinking, meditation, and concentration. Concentration that is being talked of here is actually samādhi (dissolution, union). Listening that is being talked of here is actually just hearing.

So, “Hearing is to pursue by means of sentences their import.” Hearing simply means: take in the sentence, take in the gross word, let the soundwave strike your eardrums, let your brain receive the signal. That is hearing. Let the soundwave strike your eardrum, let your consciousness receive the signal that something has been communicated to you. That much is hearing. Obviously hearing has to be there; without that things can’t even begin.

Then there is thinking. So, hear, then think about it—what does it mean to think? The Upanishad says, to think is to measure the consistency of the heard sentence, the heard input, with reason. See whether what is being said is logical. See whether what is being said is factual. See whether what is being said abides by the law of cause and effect. See whether what has been said is self-contradictory. That is thinking.

And then meditation is being talked of. “Meditation is the exclusive attention of the mind fixed on the import rendered indubitable through listening and thinking.” So, now that the heard word has passed the test of reason, so you believe in it, right? It has obtained for itself a certain credibility. You heard it, you examined it, you find it reasonable, so it has some weight. Therefore, you can give yourself to it even more.

Meditation, then, is to concentrate on, focus on what that sentence is saying. And because all of this is being referred to in a spiritual environment, therefore the sentence that you are hearing obviously has Truth as its import. What else do you hear in a spiritual milieu? All sentences that deal with Truth. So, Truth is the import of the sentence. Meditation is the mind attending only to the Truth.

So, a sentence about the Truth came to you. You first of all made yourself physically and sensually available to hear. If you are not physically available, if your ears are not open, then the beginning itself won’t take place. So, first of all you let the sentence be heard, then you critically examined the sentence and said, “At the level of reason, the sentence appears important, worthy, good enough to be taken forward.” And then you meditate it; you said, “Right, the sentence is talking of Truth. What is this Truth? I see its importance, I see its total importance. How can I be available to it?” And the more you proceed on this line, the more you find that you are insufficient. So, you give more of yourself to this process.

Seeking the Truth demands all your resources. And when all your resources are demanded, then you withdraw your resources from elsewhere. Pursuing the Truth is a giant enterprise; you will need to pool in everything that you have. So, you will have to call back your forces from the various fronts they are deployed at. You will say, “You too come in, you too come in. All of you are needed here. Something very important is happening here. You know, we are pursuing the Truth, and that requires everything that I have and much more.”

So, the attention is, then, exclusive. All your other affairs drop. You cannot be parallelly, simultaneously engaged with Truth and something else. If you are engaged with Truth and something else, then you will not have the energy to do justice to the Truth.

And in the competition between Truth and something else, the something else will always prevail. There is a clear reason: that something else is little, so it can survive even with your little dedication. That something else is small, mediocre, so how much attention does it need? Small, little. How much does Truth need? Everything.

Let’s say you have ten units of resources, and there is Truth and there is something else. Something else needs just one unit of your resources; it is small, frugal. Truth requires all ten units that you have. And you say, “Oh, I am greatly dedicated towards the Truth. I will give nine units to the Truth and one unit to something else.” In your own calculation, you have greatly favored the Truth, have you not? You are giving nine units to Truth and just one unit to something else. You are saying, “You see, I love the Truth 9:1.”

But what have you actually done? That something else will survive because one unit is sufficient for it. Truth will die down. Your pursuit of Truth will be aborted, because Truth requires all ten. Even nine is highly insufficient. That little thing requires only little. Give it one, it will keep prospering. Therefore, the Upanishad says exclusive attention. It cannot be Truth and something else.

Then, samādhi . The duality between meditator and meditation is gone; the duality between the subject and object is gone; the duality between the ego and Truth is gone. The ego has become so enamored of the Truth that it is prepared to lose its own identity. “I want That, I am looking continuously at That, so I have lost all track of myself. Do I exist? I exist now only in relation to That.”

So, first of all, the other relationships are cut off. You say, “I exist only in relation to That. That is my only identity. Who am I? Something related to That.” Everything else drops off. And slowly, you even stop saying that you are related to That; there comes a point when you say, “I am That.”

To begin with, how are you and what do you say? You keep saying, “I am related to this, I am related to that, I have a thousand relationships.” That’s the stage to begin with. What happens when after hearing and thinking and meditation, you remain related only to That? The other relationships fall off, because if you are to pursue That, then That requires everything that you have. If you give everything that you have to That, then the other things will obviously be disappointed, and they will all just get switched off and walk away.

So, now you have only one relationship. From a hundred relationships you are left with one, and finally even that one relationship no more remains a relationship, it becomes a union. So, “I am not related to That. I am That. I am related to the hundred, then I am related to just one, then I am the One.” That’s the process.